The Fine Art of Ridiculous - but Successful - PR

- tripping8

- Oct 3, 2025

- 12 min read

The history of human persuasion is a long con dressed up as progress. Nations have been built, wars justified, and empires sold not with facts but with slogans, spectacles, and the occasional holy endorsement. Civilization itself sometimes looks less like a march of reason than a never-ending carnival barker’s pitch. If you doubt it, recall that entire generations once believed leeches would cure consumption - and paid handsomely for the privilege.

Of course, the line between medicine show and modern marketing is paper thin. Today we scoff at miracle tonics, but we happily hand over our wallets for $9 bottles of “ionized water” that would have baffled the snake-oil men only by its sheer profitability. The names change, the props evolve, but the formula is eternal: astonish, provoke, seduce. To sell is not enough; one must astonish in a way that the story endures long after the product itself has gone flat.

Every so often, the audacity crosses into the sublime. A pope sipping cocaine-laced wine to cure his fatigue, or a genius of invention electrocuting an elephant to prove a point about alternating current - these are not dusty anecdotes buried in the margins of history textbooks. They are reminders that outrageous publicity has always been the favored tool of the ambitious, whether cloaked in sanctity or science. Even Paris Hilton, with her blank gaze and “That’s hot,” was simply channeling an older, more aristocratic tradition: make them look, no matter how.

Which brings us this week’s topic: the fine art of ridiculous - but successful - PR stunts. From potato fields guarded like crown jewels to fast-food wars waged through geofencing apps, the marketing world has thrived on spectacle as much as on substance. What follows isn’t a chronicle of products so much as it is a study in human appetite - for attention, for scandal, for the absurd. After all, as we’ve seen time and again, history rarely rewards the sensible.

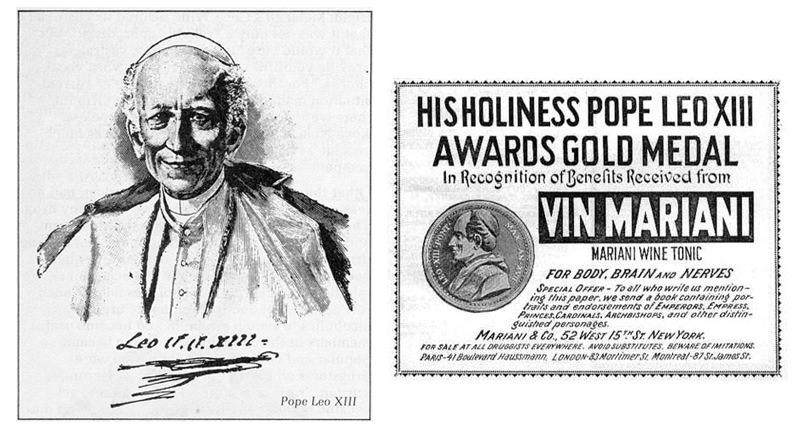

The Pope’s Little Pick-Me-Up

Pope Leo XIII was a man of deep faith, refined taste, and, apparently, a fondness for stimulants. In the late 19th century he publicly endorsed Vin Mariani, a Bordeaux wine liberally laced with cocaine, praising its restorative powers and even bestowing it with a Vatican gold medal.

For a brief shining moment, the Vicar of Christ doubled as the world’s most influential drug dealer, and sales soared accordingly. One imagines parishioners leaving Mass in unusually buoyant spirits, rosaries rattling just a bit quicker than usual.

As marketing goes, it was genius. Forget billboards, jingles, or awkward product placement - if you’ve got the pope on coke, you don’t need a billboard. The implicit message was as clear as scripture: Drink this, feel divine, and perhaps glimpse eternity while you’re at it. An indication that sanctity and stimulants make surprisingly compatible bedfellows.

One might be tempted to sneer at the gullibility of 19th-century Europeans, guzzling sanctified narcotics in the name of health. But is it so different from our own wellness gurus hawking kale smoothies, mushroom coffee, or whatever powdered nonsense currently promises transcendence in a can? Cocaine wine at least had the decency to deliver on its promise - you felt something. Today’s miracle elixirs are all placebo, no kick.

Protect the Potatoes / Potato Patrols

In 18th-century France, Antoine-Augustin Parmentier , a French pharmacist and agronomist, faced a peculiar problem: the potato.

It was plentiful, nutritious, and – unfortunately - widely despised, dismissed as fodder for livestock and the desperate. To win hearts and stomachs, Parmentier devised a bit of theater. He stationed armed guards around his potato fields, instructing them to accept bribes and conveniently look away. Soon enough, Parisians were pilfering tubers with the enthusiasm of jewel thieves.

It was a masterstroke of reverse psychology, centuries before luxury brands perfected the art. Declare something forbidden, surround it with men and muskets, and watch demand swell. The potato became less a crop than a status symbol, stolen at risk, served at table with a whiff of danger. French cuisine owes much to butter and wine, but perhaps just as much to Parmentier’s manufactured scarcity.

The irony is that what began as a desperate trick to dignify a root vegetable became a template for marketing itself: if people aren’t buying, convince them they shouldn’t be allowed to. From limited-edition sneakers to “members-only” clubs, the strategy endures. Parmentier’s potato scam was not just agricultural reform - it was the birth of exclusivity as a sales tactic, proof that nothing whets the appetite quite like a locked gate.

The Chicken Crossed the Road

In February 2018, the unthinkable happened in Britain: KFC ran out of chicken. A supply chain fiasco left hundreds of stores shuttered, outraged customers clutching their empty chicken buckets like mourners, and tabloids feasting on the absurdity.

For a fast-food empire whose very name is chicken, it was a crisis bordering on existential.

Rather than issue a groveling press release, KFC took out a full-page newspaper ad featuring its iconic red bucket, logo rearranged to read “FCK.”

Three letters, one missing vowel, and the entire debacle was reframed - not as corporate incompetence, but as a moment of cheeky British self-awareness. The public, instead of sharpening their pitchforks, applauded the joke and forgave the sin.

It was a rare case where candor triumphed over spin. By admitting the blunder with wit, KFC turned what should have been brand suicide into a textbook example of reputational jujitsu. The lesson was clear: if you want to survive disaster, don’t hide it - mock yourself before anyone else can. Especially if the alternative headline reads “Chicken Giant Chickened Out.”

A Sucker Born Every Minute

Long before user experience was a design discipline, P.T. Barnum was perfecting it with the subtlety of a pickpocket. At his American Museum in the mid-19th century, visitors found signs pointing to something called The Egress.

Imagining it to be some exotic bird or beast curious patrons dutifully followed the trail. The marvel they discovered was the sidewalk outside, the door clicking shut behind them. To see more wonders, they had to pay again.

It was both a swindle and a revelation: Barnum turned human gullibility into a recurring revenue stream. People weren’t simply buying a ticket; they were buying the chance to be tricked and then laugh about it later, once the sting of a second admission fee wore off. In Barnum’s world, disappointment was part of the entertainment, and confusion itself became a product.

The elegance of the stunt lies in its simplicity. Barnum didn’t need elaborate illusions or complicated machinery, just a sign and the public’s unshakable faith that every unfamiliar word concealed some marvel. Today we have “dark patterns” on websites, free trials that renew forever, and “click here to unsubscribe” buttons that don’t.

Barnum’s egress was their grandfather: proof that the art of fleecing the curious is timeless.

A Whopper of a Download

In December 2018, Burger King executed a stunt that was equal parts mischief and marketing genius. Dubbed the “Whopper Detour,” the scheme offered Whoppers for one cent - an irresistible price, with a catch. To unlock the deal, customers had to place their order through the BK mobile app while physically located near a McDonald’s. Suddenly, golden arches became the world’s largest billboard for the King’s crown.

It was the kind of petty brilliance fast food thrives on, a digital prank masquerading as innovation. Customers gleefully drove into McDonald’s parking lots, ordered Whoppers, and sped off to collect them from the nearest Burger King. In the process, Burger King’s app downloads skyrocketed, 1.5 million downloads in just a couple of days, while McDonald’s was reduced to playing the role of unwilling landlord.

What made the stunt work wasn’t just the bargain - it was the theater of defection. The thrill of outwitting a rival brand for a penny burger turned dinner into performance art. Burger King wasn’t selling fast food so much as fast betrayal, and millions happily played along. It was a reminder that in marketing, as in geopolitics, nothing stings quite like losing your territory.

Diamonds Weren’t Always Forever

The Great Depression of the 1930’s resulted in a problem no cartel likes to admit: too many diamonds and too little demand. Engagement rings existed, of course, but they came in all manner of stones - sapphires, rubies, emeralds - each with as much claim to sentiment as a hunk of carbon. Diamonds were a luxury that the average citizen wouldn’t consider setting money aside for. De Beers’ challenge was not to just to sell gems but to convince the world that only their gem counted.

The advertising campaign they launched in 1938 with the tagline “A Diamond is Forever” was less advertising than social engineering.

Through magazines, newspapers, and carefully planted Hollywood storylines, the diamond became synonymous with romance. By the 1940s, the slogan had become as absolute as any biblical injunction. Scarcity was a fiction, permanence was a metaphor, but both worked. Soon, proposing marriage without a diamond looked cheap, even shameful. A lump of compressed carbon became the only acceptable proof of fidelity.

Nearly a century later, the spell holds. Couples still bankrupt themselves for rocks hoarded in vaults, mistaking clever advertising for timeless tradition. What De Beers achieved wasn’t just a sales boost - it was cultural annexation. They didn’t persuade people to buy diamonds; they rewrote the ritual of romance itself, embedding their product into the very script of adulthood. The brilliance wasn’t in the stones but in the audacity: turning a surplus into a symbol, and a marketing pitch into a cultural mandate. In 1999, “A Diamond is Forever” was named as “The Slogan of the Century” by Advertising Age.

Tacos on the Moon

In 2001, Taco Bell decided to tether its fortunes to a decaying Russian space station. As the Mir prepared for re-entry, the chain announced that if any debris struck a massive 40X40 floating “bullseye” they had placed in the Pacific Ocean, every American would receive a free taco.

It was part lottery, part lunacy, and entirely irresistible to the press. Newscasts that normally ignored fast food suddenly ran footage of Taco Bell’s bullseye bobbing in the waves.

The outcome, of course, was predictable: Mir missed the target, the tacos remained full price, and the franchise didn’t have to declare bankruptcy (though they did purchase an insurance policy just in case MIR hit the bullseye). But the gamble paid off spectacularly in publicity. Taco Bell claimed the stunt generated over a billion media impressions worldwide, a reach most ad campaigns could only dream of. Even NASA fielded questions about tacos during press briefings.

What the brand proved is that spectacle drives attention. No one seriously expected to be showered in beef and cheese from orbit, but millions followed the story anyway. For the cost of a giant target and some creative nerve, Taco Bell turned the slow-motion funeral of a Soviet relic into a global advertisement for Crunchwraps. In marketing terms, Mir may have burned up in the atmosphere, but Taco Bell’s stunt stuck the landing.

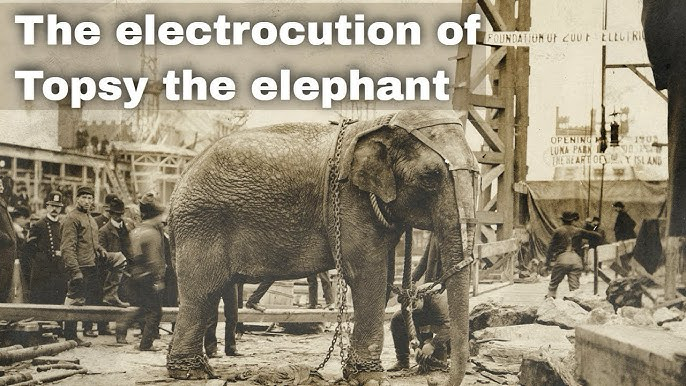

The Elephant in the Room

At the turn of the 20th century, Thomas Edison was less the kindly inventor of childhood textbooks than a ruthless showman fighting for market dominance. His rival Nikola Tesla had championed alternating current (AC), a system more efficient and practical than Edison’s direct current (DC). Rather than concede, Edison launched a smear campaign dressed up as public safety.

His method: stage grisly demonstrations of animals electrocuted with AC, proof - he claimed - that Tesla’s system was too dangerous for human use.

The most infamous case came in 1903 with Topsy, a circus elephant slated for execution after a string of unfortunate incidents with her handlers. Edison’s team saw opportunity. Before a crowd at the Coney Island Amusement Park, they ran 6,600 volts of alternating current through her, killing her in less than a minute. The event was filmed, the footage distributed, and Edison expected the message to spread: AC equals death. It was the turn-of-the-century equivalent of a viral campaign, only with the cruelty of a public execution at its core.

As propaganda, it failed. Tesla’s alternating current went on to power cities, while Edison’s reputation carried the stain of grotesque theatrics. But the episode is revealing: Edison understood that the contest wasn’t just about technology - it was about narrative. To win, he had to turn science into spectacle, fear into persuasion. In the process, he proved a truth as enduring as the lightbulb: the line between invention and public relations can be perilously thin, and genius is never immune to pettiness when markets are at stake.

Pancakes vs Burgers

In June 2018, IHOP announced it was rebranding as “IHOb” - the International House of Burgers. For weeks they teased the mysterious “b,” letting speculation swirl online. When the reveal came, it triggered exactly the kind of chaos the chain had hoped for: confusion, mockery, outrage. Loyal pancake devotees fumed, while competitors like Burger King and Wendy’s gleefully piled on with their own trolling campaigns. In short, everyone was talking about IHOP - for the first time in years.

On its face, the stunt looked absurd. Why would a diner synonymous with pancakes abandon its most valuable asset for a half-hearted foray into burgers? But that was the genius: the goal wasn’t a permanent identity shift, it was attention. Within weeks, IHOP clarified that the name change was temporary, a publicity trick to promote a new burger line. Behind the smoke and social-media fury, the results were undeniable - burger sales more than doubled, and IHOP had successfully inserted itself into the fast-food conversation without buying a single Super Bowl ad.

As PR strategy, it was a masterclass in manufactured outrage. By toying with its own brand identity, IHOP weaponized consumer loyalty, knowing full well the internet would turn the joke into free publicity. It worked because the move was both ridiculous and reversible: they could always go back to pancakes, but in the meantime, the world had been reminded that IHOP served lunch and dinner too. In the noisy marketplace of fast food, subtle campaigns vanish. Absurdity, however, trends.

Beer Trivia

In 1951, Sir Hugh Beaver, managing director of Guinness, found himself in a familiar predicament: an argument in a pub. The question - what was the fastest game bird in Europe? - proved unanswerable on the spot in the pre-Google era.

Beaver realized that such disputes were not only common but a kind of pub pastime, and that Guinness could profitably insert itself as the arbiter of record and fact. His solution was simple and ingenious: publish a book of definitive answers, stamp the Guinness name on the cover, and hand it out in pubs alongside the beer.

The first edition of The Guinness Book of Records appeared in 1955, and what began as a promotional freebie quickly outgrew its purpose. By the following year it was a bestseller, and within a decade it had become a global publishing franchise, translated into dozens of languages. The marketing stunt had slipped its leash, transforming from a clever piece of branded trivia into a cultural institution in its own right. The book became as much a staple of school libraries and holiday gifts as the beer was of pub counters.

What made the campaign so effective was its seamless alignment with the product. Guinness didn’t just sell stout; it sold itself as the official referee of drunken arguments. By providing the official answer book to those arguments, the brand made itself indispensable. Unlike many PR stunts that vanish once the headlines fade, this one became self-sustaining. Guinness didn’t just sell more pints - it installed itself as the custodian of human eccentricity, one record at a time.

Talent Not Required

When The Simple Life premiered in 2003, it was meant as a novelty: two pampered heiresses - Paris Hilton and Nicole Richie - struggling through menial tasks like milking cows and flipping burgers.

The joke was supposed to wear thin after a single season. Instead, Hilton’s blank stare, carefully cultivated aloofness, and endlessly repeated catchphrase - “That’s hot” - became an unlikely cultural phenomenon. Before memes existed, she was one; before influencers were a career path, she was living proof that you could monetize attention itself.

Whether accidental or calculated, Hilton turned the absence of talent into the product. She wasn’t selling music, or films, or business ventures - she was selling herself as a brand, a lifestyle, a walking billboard for a new kind of celebrity. Critics dismissed her as vapid, but that was the point: she had cracked open the marketplace for fame unmoored from achievement. Her very uselessness became useful, a marketing engine that filled tabloid pages and fueled reality TV spin-offs.

The ripple effect was enormous. Hilton’s formula - attention as currency, scandal as strategy - created the blueprint for a generation of reality stars and influencers. Without her, there is no Kardashian empire, no TikTok fame factory, no endless parade of “personal brands” hawking diet teas and teeth whiteners. She didn’t just stumble into stardom; she pioneered a new genre of PR stunt, one where life itself was the advertisement. For better or worse, Paris Hilton wasn’t the punchline - she was the prototype. Apologies.

It's a Fine Art Indeed

What ties all these stories together isn’t genius so much as audacity. A potato field with armed guards, a pope on coke, a chance to see “the egress” - none of it makes sense on paper. But that’s the point. The stunts worked because they didn’t play by the rules. They broke them, laughed about it, and left the competition scrambling to explain why they hadn’t thought of it first.

The safe campaigns, the cautious slogans, the committee-approved branding decks, the earnest press releases - those vanish into the void. Nobody remembers the ad that played it safe. We remember the elephant, the taco bullseye, the pancake house pretending to be a burger joint. These weren’t just marketing ploys; they were cultural pranks, gambles so outrageous they became folklore.

And maybe that’s the most honest thing about advertising: it doesn’t pretend to be noble. What’s striking, leafing through this parade of hucksters, heiresses, and poultry shortages, is how little has changed. The trappings evolve - what was once a circus poster is now a viral tweet - but the hustle remains the same. Advertising doesn’t care about dignity. It never has. It cares about the spectacle, about worming its way into your head until you can’t stop repeating the story. If it takes shock, or humor, or outright deception, so be it. The product is almost incidental.

So yes, the whole enterprise is ridiculous. But ridiculous works. It worked in the 18th century, it worked in the 20th, and it still works now. Make them laugh, make them gasp, make them angry enough to argue. Because, if they’re still talking about you when the drinks run dry, you’ve already won. History doesn’t reward the sober or the sensible. It rewards whoever had the nerve to try something ridiculous - and just managed to get away with it.

#MarketingStunts #PRWins #MarketingMadness #AdvertisingLessons #ViralCampaigns #MarketingStrategy #AdvertisingStunts #PublicRelations #RidiculousButSuccessful #PR #ParisHilton #DeBeers #diamonds #potatoes #Whoppers #BurgerKing #TacoBell #IHOB #IHOP #Guinness #beer #KFC #FCK #Topsy #Edison #Tesla #ac/dc #VinMariani #DiamondsAreForever #anyhigh

Okay so I remember the Burger King promotion and thought it was brilliant then! It still is.

I really think that the KFC marketing guys were brilliant! Be honest, what a novel concept!

My friend and former boss was the CEO who gave the go ahead to IHOb! I remember calling him and saying WTF are you thinking! He just laughed and asked … when was the last time you talked about IHOP….. I didn’t get it, but its genius was so beautiful.

Thanks for the laugh!

Oh you and I need to speak about my Master's thesis including the father of PR Edward Bernays. You missed some of his good ones like placing cigarettes in the mouths of suffragettes to get women to smoke: 50 years later the tagline you've come a long way Baby still empowers women to smoke in more ways than one. The other famous one is introducing women to cake mixes which fell flat because women thought it was for lazy housewives. Now we add an egg. 😂