Olympics, Weird and Wonderful

- tripping8

- Aug 16, 2024

- 12 min read

The Paris Olympics have just wrapped up, leaving the world in a state of collective awe and adrenaline withdrawal. The precision of Simone Biles, the blistering speed of Noah Lyles, and the endless tales of triumph and heartbreak have made these games a worthy successor to over a century of Olympic history.

But as we bask in the afterglow of these exhilarating performances, it’s worth taking a moment to reflect on the Olympics of yesteryear - an era when the games were not just a showcase of human athleticism but also a curious parade of oddities.

Because, beyond the dazzling feats and record-breaking moments, there’s another side to Olympic history - one that’s less about glory and more about sheer absurdity. The Olympics we know today, with its sleek arenas and cutting-edge technology, is a far cry from the days when athletes competed in events that now seem downright bizarre. As we delve into the history of the Games, we’ll uncover a world where the line between sport and spectacle was often hilariously blurred.

In today’s post, we’ll look back on a time when the Olympics were as much about eccentricity as they were about excellence. From events that made you question the sanity of the organizers to competitions that seem better suited for a village festival than in the world’s premier sporting event, we’ll explore some events that are no longer included along with some of the strangest sports ever to grace the Olympic stage. It’s a reminder that while the Games have evolved, their history is sprinkled with moments that are as bewildering as they are entertaining.

Chariot Racing (c. 684 BC - 393 AD): The first Olympic Games in ancient Greece took place in Olympia around 776 B.C. and likely included only one event: a foot race. Over time, organizers added more sports to the Olympics, including chariot racing. Starting around 684 B.C., drivers raced each other in fragile, rickety, horse-drawn chariots at the Olympics, sometimes violently crashing into one another.

Only boys and men could participate in Olympic events as athletes, but wealthy women could sponsor chariots. Because it was a chariot’s sponsor who received the victory title, not the racer himself, this was the only way women could “win” at the Olympics. The first known woman to do so was the Spartan princess Cynisca, whose chariot was victorious at the Olympics in 396 and 392 B.C.

So why don’t we see chariot racing in the modern Olympics?

Because, over time, the thrill of watching high-speed crashes lost its charm? Not likely. Or maybe it was the realization that awarding a gold medal to someone who merely footed the bill wasn’t quite in keeping with the Olympic spirit? More likely it’s because the insurance premiums just became too astronomical. In any case, chariot racing was quietly retired, leaving behind a legacy of dust, danger, and the occasional wealthy woman who, for a moment, tasted victory without ever having to break a sweat.

Plunge for Distance (1904): Imagine a swimming competition where you dive in and then just float like a dead fish. In the 1904 Olympics in St. Louis, Missouri that’s what some athletes did. Distance plunging required swimmers to dive off a platform into the water and travel as far as they could in 60 seconds without moving any limbs.

Three Americans swept the podium: William Dickey with 62.5 feet (19.05 meters), Edgar Adams with 57 feet (17.53 meters), and Leo Goodwin at 56.7 feet (17.37 meters). The sport didn't require much athleticism or skill, and spectators were basically watching someone float in a pool. Needless to say, it didn't last as an Olympic event after 1904.

Rope Climbing (1896, 1904, 1924, 1932): Back in the day, climbing a rope wasn’t just a P.E. class nightmare; it was part of the Olympic gymnastics program. Rope climbing was included in the first modern Olympic Games in Athens, Greece, in April of 1896 and continued, off and on, through the 1932 games.

Competitors had to climb the rope in the fastest time possible, starting from sitting on the floor and using only their hands. In addition to speed, style points were included in the scoring. In one of the most exciting races, American gymnast George Eyser, who competed with a wooden leg, won gold in the 1904 St. Louis Olympics.

Tug of War (1900-1920): This playground classic was an actual event in the ancient Greek Olympics and was revived for five modern Olympic games.

Teams of eight would haul against each other in a test of brute strength, the first to pull the other team across a six-foot marker won. If either side failed to do so, judges gave the struggle a further five minutes and then declared the team who had made the most progress the victors. The 1908 Olympics in London saw one of the more peculiar displays in this event when the British team, always composed primarily of burly police officers from Liverpool, showed up wearing extraordinarily heavy boots.

These boots, which weighed so much that they could hardly walk in them, gave the team an undeniable advantage - they were nearly impossible to budge. Unsurprisingly, the British team dragged their competitors across the line with relative ease, sparking complaints of unfair advantage, though the rules at the time allowed it.

Standing High & Standing Long Jumps (1900-1912): These two events are a lot like today’s equivalent, just without the running start. In these events, instead of running to propel them forward, athletes could only swing their arms and bend their knees to provide force.

While these events might seem better suited to kangaroos, it must have been a spectacle that looked equal parts impressive and absurd, with athletes straining every muscle to defy gravity in the most straightforward – and punishing – way possible. Incredibly, an American athlete Ray Ewry, who was wheelchair bound with polio as a child, won gold in 1900, 1904, and 1908 in both events.

He became known as “The Human Frog.” The event was dropped from the Olympic program after 1912, perhaps because someone finally realized that, while impressive, watching grown men attempt to jump straight up and down wasn’t exactly the pinnacle of spectator excitement.

Underwater Swimming (1900): The 1900 Paris Olympics were a veritable treasure trove of Olympic oddities (more to follow). They included one of the most perplexing events ever conceived: Underwater Swimming. Competitors had to swim as far as they could underwater in the River Seine, earning points for both distance and time spent submerged. Each swimmer received one point for every second they stayed underwater and two points for every meter they covered.

It was an aquatic contest that seemed to prioritize stealth over speed.

From a practical standpoint, the event made some sense - after all, breath control is a vital skill for any swimmer. But as a spectator sport, it was less than thrilling. With swimmers disappearing beneath the surface, the audience was left staring at an empty river. All the audience could see were a few bubbles, perhaps a fleeting shadow, and then more bubbles. The excitement of watching a race was replaced with the odd sensation of waiting for someone – anyone - to resurface.

Frenchman Charles Devendeville won the gold by staying underwater for one minute and eight seconds, covering the maximum distance of 60 meters. He narrowly beat fellow Frenchman Andre Six, who stayed submerged for one minute and five seconds. Despite the impressive displays of endurance, it’s little wonder that Underwater Swimming didn’t make a repeat appearance in subsequent Games - its blend of suspense and utter tedium proved too strange even for the early Olympic organizers.

Live Pigeon Shooting (1900): Yet another questionable event on the roster of the 1900 Paris Games. While competitors typically shot at disc-shaped targets called clay pigeons, the 1900 Games went with livelier targets – real pigeons. Not exactly in keeping with the Olympic spirit of peace and unity.

The event was as chaotic as it was grim. Participants stood with shotguns at the ready, aiming to down as many birds as possible. With every round, a flurry of feathers filled the air, as over 300 pigeons eventually met their end in the name of sport. In a 1988 article about the 1900 Paris Olympics, American sports historian Andrew Strunk wrote dryly, "The idea to use live birds for the pigeon shooting turned out to be a rather unpleasant choice. Maimed birds were writhing on the ground, blood and feathers were swirling in the air and women with parasols were weeping in the chairs set up nearby."

The scene must have been a macabre spectacle: onlookers witnessing a relentless barrage of gunfire and a rain of lifeless birds falling to the ground. One can only imagine the carnage - a field littered with feathers, blood, and the occasional still-twitching victim, all while the crowd cheered. The gold-medal winner, Belgian Leon de Lunden, killed 21 pigeons.

Club Swinging (1904, 1932): Think rhythmic gymnastics meets caveman. This now-forgotten event in Olympic history featured in the 1904 and 1932 Games. It involved athletes performing elaborate routines with heavy wooden clubs, swinging them in intricate, fluid patterns around their bodies. The clubs resembled oversized, maracas or the kind of weapon a caveman might wield, but instead of bashing anything, the objective was to create a mesmerizing display of coordination, strength, and grace.

The competitors, clad in their athletic gear, would take to the stage and begin a performance that looked like a cross between a dance and a circus act. The clubs twirled and whirled, tracing elaborate arcs through the air as the athletes demonstrated their dexterity and control. But unlike the lightweight apparatus used in modern rhythmic gymnastics, these clubs were no joke - they were heavy. Spectators likely watched with a mix of fascination and tension, half-expecting a club to go flying in their direction at any moment.

Two Paris Olympic Races Gone Wrong (1900 & 1924): The 1900 Paris Olympic Marathon was less a showcase of athletic prowess and more an urban adventure. It involved a confusing, poorly marked course that went straight through the streets of Paris. Many runners took wrong turns, and, in some places, the course overlapped with the commutes of automobiles, animals, bicycles, and pedestrians joining in for fun. Amid the course confusion, fifth-place finisher Arthur Newton claimed that he had finished first because he never saw anyone pass him. Even worse, the race was run at 2:30 in the afternoon in July heat that reached 102 degrees (38 C). The local favorite, Georges Touquet-Daunis, ducked into a café to escape the heat, had a couple beers, and decided it was too hot to continue.

At the 1924 Paris Olympics, the cross-country course included an obstacle not listed in the official guide - an energy plant giving off poisonous fumes.

The winner, nine-time gold medalist Paavo Nurmi, got by unscathed, but nearly everyone else staggered onto the track dizzy and disoriented. On the roads, the carnage was significantly worse, as runners were vomiting and overcome by sunstroke. The Red Cross spent hours searching for all the runners who’d collapsed on the side of the road.

Stockholm’s Cycling Road Race Leads to Injuries (1912): Sweden was unable to build a velodrome for the 1912 Olympics and wanted to cancel cycling all together. At the deliberations leading up to the games, the British protested the cancellation and demanded a road race despite warnings by the Swedish delegation that their roads were in no shape for such an event. The Swedish eventually capitulated and opted to stage a race on the same circuit as their annual road race the Malaren Rundt.

At 315 kilometers, this course was over 6 times the length of the average Olympic road race. The real problem, however, was that this 10-hour race began at 2 AM, which made conditions rather dangerous. Fortunately, there were only two major casualties, but neither was pretty: one Russian rider plunged into a ditch and lay unconscious until discovered by a local farmer while another, Sweden's Karl Landsberg, was hit by a car shortly after the start and dragged along the road for some distance before being rescued.

Despite these harrowing moments, the race continued, with French cyclist Gustave Garrigou emerging victorious and claiming the gold medal.

Motorboating (1908): Motorboating, a sport that required zero athletic skill, appeared in the Olympic Games for one year only. The men-only motorboating event took place in September at the 1908 London Olympics and required competitors to race around a course five times.

The event quickly proved to be a test of patience rather than speed. Motorboating, as it turned out, had a few teething problems. The boats, while ambitious, were prone to stalling. The average speed barely hit 20 mph, and spectators could hardly see the competition from the shore. Rather than witnessing high-speed chases, spectators were treated to a spectacle of boats sputtering to a halt and being dragged back into action. By the end of the competition, it was clear that motorboating was not quite the electrifying spectacle the organizers had hoped for.

Great Britain won two of the three motorboating categories with France also winning one category.

Croquet (1900): Croquet made a brief and baffling appearance in the 1900 Paris Games. A sport originally favored by English aristocrats for leisurely afternoons on manicured lawns, croquet's foray into the Olympics was as short-lived as it was peculiar. It’s not every day that an event designed to evoke genteel relaxation finds itself thrust into the rigorous world of competitive athletics.

There were four croquet events: one ball singles, two ball singles, doubles, and singles handicap. The French won all of the croquet events because, well, they were the only country to compete in the event. Two French women, Madame Brohy and Mademoiselle Ohnier, competed in croquet with the men, making them the first female Olympians (female sponsored chariot racers notwithstanding).

The sport’s charm was evidently lost on the international community given that only one spectator showed up, making the whole experience seem like a peculiar form of high-society performance art. Due to lack of spectatorship and because the sport had “hardly any pretensions to athleticism,” it was discontinued after 1900.

The Longest Marathon in Olympic History (1912-1967): In the annals of Olympic lore, Shizo Kanakuri’s marathon story from the 1912 Stockholm Games stands out as a blend of drama, endurance, and a truly one-of-a-kind ending. Born in a rural Japanese town in 1891, Shizo Kanakuri ran eight miles a day to and from school, and in the marathon trials for the 1912 Stockholm Olympics held in November 1911, he is said to have run a time of 2h 30m 33s, then believed to be a world record (although the course was 25 miles instead of the regulation 26.2 miles).

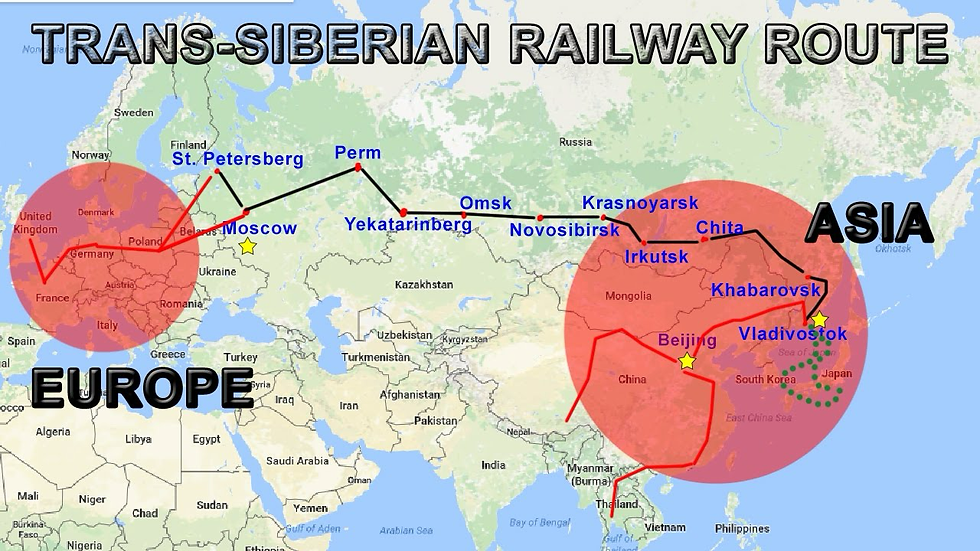

Kanakuri was chosen as one of two Japanese athletes to compete in Stockholm and raised the 1,800 yen required to get from Japan to Sweden, no mean feat at the start of the twentieth century. It took him eighteen days to reach Stockholm including traversing almost the entire length of the Trans-Siberian Railway.

The race took place in the middle of a brutal heatwave, dozens of competitors dropped out and one, Portuguese Francisco Lazaro, died during the race. The 1908 Olympic marathon gold medalist called the event a ‘disgrace to civilization.’

Kanakuri himself suffered from hyperthermia – overheating – and stopped after about sixteen miles. He found his way into a party in someone’s garden where it’s said he drank orange juice for an hour. Embarrassed by his perceived failure, he quietly went back to Japan. It’s thought he told race officials he was leaving but the Swedes somehow recorded him as a missing person for over fifty years. Then something amazing happened.

In 1967, a Swedish television program managed to track Kanakuri down, he was working as a geography teacher in Japan. They invited him back to Stockholm to finish the race he started, and he jumped at the chance. So, on March 20, 1967, Shizo Kanakuri finished the marathon, and his time was officially listed in the records of the Olympic Games as 54 years, 8 months 6 days 5 hours 32 minutes 20.3 seconds.

As well as finishing the race, he went back to the same house and drank orange juice with the son of the family who invited him in.

Kanakuri died in 1983 aged 92 and is today considered, and celebrated, as the father of marathon running in Japan.

And that story of endurance and redemption seemed like a nice place to wrap up our look at the Olympics, weird and wonderful.

The Olympics, for all their polished, prime-time glory, are just as much about the glorious missteps as they are about the triumphs. It's tempting to get caught up in the grandeur - the world records shattered, the tears of triumph, the stories that make you believe in the impossible. But, as we’ve seen, this isn’t just a stage for the world’s most polished athletes but also a theater of the curious, where the line between sport and spectacle often blurred into something hilariously memorable.

Because for every Simone Biles flipping through the air with perfect grace, there was a Shizo Kanakuri taking 54 years to finish a marathon. For every high-tech stadium filled with laser-precise timing systems, there were once athletes hurtling through streets cluttered with cars, pedestrians, and the odd stray dog, just trying to find the finish line. These moments of chaotic brilliance remind us that the Olympics aren’t just about the finest displays of human ability but also about the magnificent messiness of it all.

So, as we bid farewell to another Olympic Games, lets raise a glass to the chariots that crashed, the pigeons that never saw it coming, and the long-forgotten athletes who swung clubs, climbed ropes, and floated in pools like they were auditioning for the strangest circus ever conceived. The Games may have evolved, but they’ll always carry a hint of that delightful chaos - a reminder that sometimes, the journey is just as entertaining as the destination.

I really love the Olympics, even through their missteps. It’s so funny how things have changed from shooting other Sunday best to high tech swimwear to eliminate drag….

I remember having to do the standing long jump in PE class! Whew, I am old!

Glad they got rid of a lot of the events …. Croquet???? Seriously has to be the most boring, well so is the distance plunge.

I personally think the breaking event should never be brought back and they should instead bring back Chariot racing!!!!

Ben Hur was and is one of my favorite movies of all time (of course the Godfather runs neck and neck) and my favorite scene I the Chariot race. Imagine my disappointme…