Men in Wigs

- tripping8

- Aug 15, 2025

- 12 min read

There are certain mysteries of human history we no longer question. Why did we build pyramids? Why did we invent mayonnaise? Why did we decide that powdered sugar on fried dough was a breakfast item? These are the quiet decisions that made us what we are - beautifully irrational, extravagantly insecure, and always, always reaching for the nearest ornament to mask the inevitable collapse.

Because there is no tragedy quite like the mirror. It waits for us with the patience of a priest and the accuracy of a tax auditor. We conceal, we contour, we comb creatively. Hairlines inch backward and we pretend not to notice. Vanity may be a sin, but in most civilizations, it’s also been a full-time job - one with a dress code, a scent, and, more often than not, an enormous price tag.

Just look at our species’ compulsive relationship with adornment. We hang rocks from our ears, burn ourselves in the sun for color, and pierce things that - in saner eras - were better left unpierced. This is not about utility. This is about theater. Social camouflage. We’ve stapled identity to fabric, class to tailoring, and sex appeal to the angle of a hat brim. Civilization, it turns out, is just accessorizing with rules.

But the thing about rules is that someone’s always breaking them. And the thing about style is that someone’s always trying too hard. Somewhere between the birth of silk stockings and the demise of codpieces, we passed through an age where personal presentation stopped being about survival and started being about spectacle. That’s when things got weird. That’s when things got powdered.

So no, this isn’t a long-lost Mel Brooks sequel:

No, it’s a look at the curious case of the male wig: a tale not just of fashion, but of fear. Fear of age, of irrelevance, of scalp. It’s a history tangled in politics, class, vanity, and lice - sometimes all at once. From pharaohs in linen-laced headdresses to powdered judges who still haunt British courtrooms, the wig has had many lives. And, like most things men fear losing - power, hair, dignity - it left quietly, without warning, and with no clear exit strategy.

Wigging out in the Desert

In ancient Egypt, personal grooming was less a matter of vanity and more a matter of survival. When you live in a climate where your scalp could fry an egg by noon, the idea of letting nature take its course - follicularly speaking - wasn’t just uncomfortable, it was unsanitary. The Egyptians had little patience for lice, sweat, and the general indignities of a hairy head under the desert sun. So, they shaved. Everyone. Men, women, priests, peasants - bald was not just beautiful, it was basic hygiene.

But being healthy and hairless did not remove vanity. Enter the wig. A sculpted status symbol made from human hair, sheep’s wool, and the occasional plant fiber. These were often stiffened with beeswax and perfumed with melting cones of scented fat that slowly melted down the scalp throughout the day. The wealthier you were, the taller and more absurd your wig. It wasn’t just sun protection - it was status. A glossy black mass of braids and beads could do what a dozen well-placed amulets couldn’t: announce your position in the social food chain.

By the time the trend reached its peak, wigs were less about sweat management and more about theater. The taller and more intricately braided your wig, the closer to godliness - or at least to the pharaoh’s inner circle. Certain styles were reserved for priests, others for nobility, and the very best wigs - the blackest, shiniest, most human-haired of them all - were the ancient equivalent of a Rolex, a Bentley, and a verified blue checkmark rolled into one.

A man could be bald as a melon, but with the right wig, he could still enter a room like he owned the Nile.

Rome Wasn’t Built on Real Hair

Blonde was not a Roman color. At least, not naturally. The olive-toned, dark-haired citizens of the empire may have conquered half the known world, but when it came to hair, their tastes leaned distinctly…barbarian. Germanic tribes, with their pale features and sun-bleached locks, were considered uncivilized in almost every way - except, ironically, for their scalps. Roman men, particularly those in the upper crust, became enamored with blonde hair, and when dyeing didn’t work they turned to the next best thing: wigs made from the hair of their enemies.

Yes, this was the golden age of cultural appropriation - quite literally. Roman generals would return from military campaigns not only with new territories but with a fresh supply of fashionable follicles. Enslaved German women were routinely shorn for their hair, which was then washed, bleached, and expertly transformed into blonde wigs for Rome’s high society men. Wearing one was a status symbol, a statement of wealth, conquest, and aesthetic refinement - with more than just a whisper of trophy-hunting.

But vanity in Rome, as with everything else, came with contradictions. While senators and orators wore their scalp-helmets to gladiatorial games and public baths, Roman philosophers like Seneca sneered at the fashion as moral decay in fiber form.

Still, for many Roman men, the appeal was hard to resist. You could be aging, bald, and morally bankrupt - but with the right blonde wig, you could still stroll the Forum like a demigod. Because in Rome, real power might have come from military might, but public respect? That came from someone else's hair.

French Fluffery

Louis XIII of France (reigned 1610–1643) was many things - king, patron of the arts, half-hearted hunter of political conspiracies - but follicularly blessed he was not. By his mid-twenties, the young monarch was already losing ground on the northern front, his hairline retreating faster than his armies ever would. In an age when a thick head of hair was a public declaration of virility and divine favor, baldness was a branding problem. So, sometime in the 1620s, Louis XIII began wearing elaborate wigs to conceal the truth - not the powdered pompadours we now picture, but more restrained creations made of real human hair, meticulously curled and brushed to simulate youth.

It worked. What began as royal camouflage quickly metastasized into a court-wide contagion of artificial hair. By the time Louis XIV inherited the throne in 1643, wigs were no longer just a cosmetic fix; they were a language of power. The Sun King took his father’s modest solution and supercharged it into an art form.

His court in Versailles became a follicular arms race - towering, perfumed, and increasingly impractical. The perruque, as the French called it, evolved from a discreet covering into a full-body statement, often cascading past the shoulders in glossy, symmetrical waves.

At its height in the late 17th century, a good wig could require the hair of several donors and cost as much as a year’s wages for a servant.

This wasn’t just vanity; it was policy. Court etiquette under Louis XIV demanded constant display, and wigs became as essential as silk stockings and powdered faces. Ministers, ambassadors, generals - anyone who mattered - wrapped their ambitions in curls, sometimes multiple times a day.

By the early 18th century, the look had spread across Europe, adopted by monarchs, judges, and aristocrats from London to Vienna. What began with a king’s bald spot ended up defining an era - proof, perhaps, that history can pivot on the smallest of vanishing hairlines.

It Was All About the Lice, Really

Of course, the towering forests of curls at Versailles weren’t just about vanity. Beneath the powder and perfume, there lurked a far more pragmatic consideration - one rooted in the very real, very itchy realities of 17th- and 18th-century life. Europe, for all its silk and candlelight, was still a place where lice, fleas, and the occasional scabies outbreak were an unglamorous fact of existence.

Hair - particularly long hair - was a perfect breeding ground. Wigs, ironically, offered a form of pest control. You could remove them at night, boil the linen lining, even fumigate them with aromatic herbs or mercury-based concoctions, while keeping your own scalp closely cropped and less hospitable to unwanted guests.

By the early 1700s, wig hygiene was practically its own science. In France, wog makers not only curled and powdered hair but also maintained it with a ritual precision that would shame most modern barbers. Wigs were cleaned and de-loused regularly, their perfumes masking the pungent residues of vinegar rinses and camphor treatments. Some men kept multiple wigs in rotation: one for formal court appearances, one for daily business, and one — inevitably — for hunting or travel, where dust and insects were most aggressive.

In England, wig boxes lined with cedar shavings became a gentleman’s defense against moths and mites, while across the Channel, scented pomades did double duty as hair styling aids and insect repellents.

So, what began as a royal indulgence became, in part, a public health measure. The French court might have dazzled the world with cascading ringlets and clouds of scented powder, but those extravagant wigs were also armor against a far less dignified enemy - the crawling, scratching reality of pre-modern hygiene. It turns out the age of elegance was also the age of pragmatic pest management.

And for all the snickering we might do from the comfort of our medicated shampoos, one has to admit: it was a clever bit of problem-solving disguised as fashion.

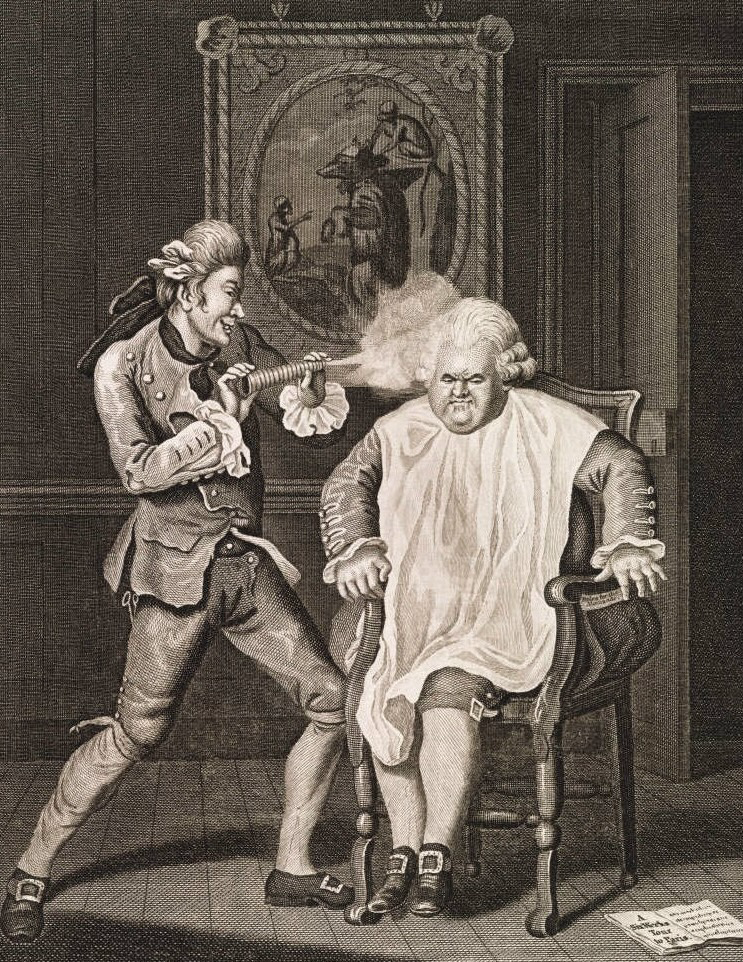

The Great Powder Tax

By the late 18th century, Britain had perfected the art of conspicuous follicular display. Gentlemen - particularly those of the upper crust - strutted about with carefully dressed wigs, heavy with flour-based powder scented with lavender or orris root. It was less about cleanliness and more about signaling that you could afford a personal valet to maintain what was essentially a frosted layer cake for your skull.

But in 1795, Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger - on the hunt for new revenue streams to fund Britain’s costly wars against Revolutionary France - saw an opportunity sitting right there on every aristocratic head.

The Hair Powder Act of 1795 slapped an annual tax of one guinea (about £1 and 1 shilling - in today’s money, roughly £100!) on anyone wishing to continue wearing powdered hair. There were exemptions for the royal family, military officers, and members of the clergy, but for most civilians, it was pay up for the privilege of dusting your head with refined wheat, or powder down.

The effect was both immediate and humiliating for wig culture. Those clinging to their powder - now nicknamed “guinea pigs” by the press - found themselves mocked as outdated and vain. Younger men, keen to appear modern and thrifty, abandoned wigs altogether in favor of their own, unpowdered hair. By the first decade of the 19th century, powdered wigs had all but vanished from polite society, surviving only in certain ceremonial roles - judges, barristers, bishops - like some strange, powdered fossil of a more flamboyant age.

Judging by the Wig

The British legal wig - that peculiar blend of matted horsehair and powdered tradition - began its career in the late 17th century, when wigs were still the height of continental fashion. Charles II, back from exile in France in 1660, brought with him both a fondness for French court style and an unspoken rule: if you wanted to be taken seriously in London’s upper echelons, you’d better be wearing hair that didn’t grow from your own head.

Judges and barristers followed suit, adopting wigs not merely for style but for gravitas. A man in a peruke was not just a man; he was an institution, and institutions, as everyone knows, look better in horsehair.

By the mid-18th century, wigs had fallen out of fashion for the everyday gentleman, but the British legal profession clung to them like a drowning man to a barrel of rum. The reason was partly status - nothing says “I speak for the Crown” quite like a starched white mop perched atop your skull - and partly the symbolism of anonymity.

The wig rendered its wearer a sort of legal ghost, subsuming the man into the role. It was never you making the argument, but The Law itself. And if The Law looked a bit like your uncle after a night in the hayloft, well, that was a small price to pay for impartiality.

Remarkably, the tradition has survived into the 21st century, despite repeated calls for modernisation. Courtrooms from London to Wellington still host their share of bewigged barristers, even as air conditioning and polyester suits have replaced the draughty chambers and heavy robes of their ancestors.

Defenders argue the wig maintains continuity, dignity, and a healthy separation between lawyer and client. Critics point out it’s essentially an overpriced, glorified mop that costs upwards of £600 and smells like an Edwardian attic after a wet spring. But like so many British institutions, the legal wig endures - part costume, part ritual, part stubborn refusal to admit that times have changed.

American Wiglessness

By the late 18th century, powdered wigs were still the European symbol of power and propriety - a kind of hair-based handshake between aristocracy and authority. But across the Atlantic, something in the colonial wind was changing. Practicality played its part: summers in Philadelphia or Virginia were every bit as oppressive as Paris in July, and the idea of wearing a wool-and-horsehair beehive dusted with flour under a blazing sun struck the new Americans as unnecessary torture. Add to that the growing cost of imported hair powder (already taxed to absurdity in Britain) and the sheer inconvenience of maintaining a wig on the frontier, and wigs began to feel less like status and more like ballast.

But the real break was political theater. The American Revolution wasn’t just about severing ties with the Crown; it was about shedding the trappings of Old World elitism. George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and John Adams all wore their natural hair, powdered perhaps, but un-wigged.

A subtle visual declaration that authority could come without an artificial halo of horsehair. Benjamin Franklin, never one to pass up a good PR move, leaned into his image as the practical, unpretentious philosopher, appearing in simple spectacles and natural hair even in the most glittering courts of Europe.

By the 1790s, wig-wearing in America was mostly the domain of older Loyalists and a few clergymen. Everyone else embraced what we might now call "revolutionary realness" - hair that grew from their own scalps, tied back in queues or left in loose, powder-dusted curls. In a young republic obsessed with virtue and self-reliance, the wig came to symbolize everything they’d fought against: hierarchy, inherited privilege, and, frankly, the smell of mothballs.

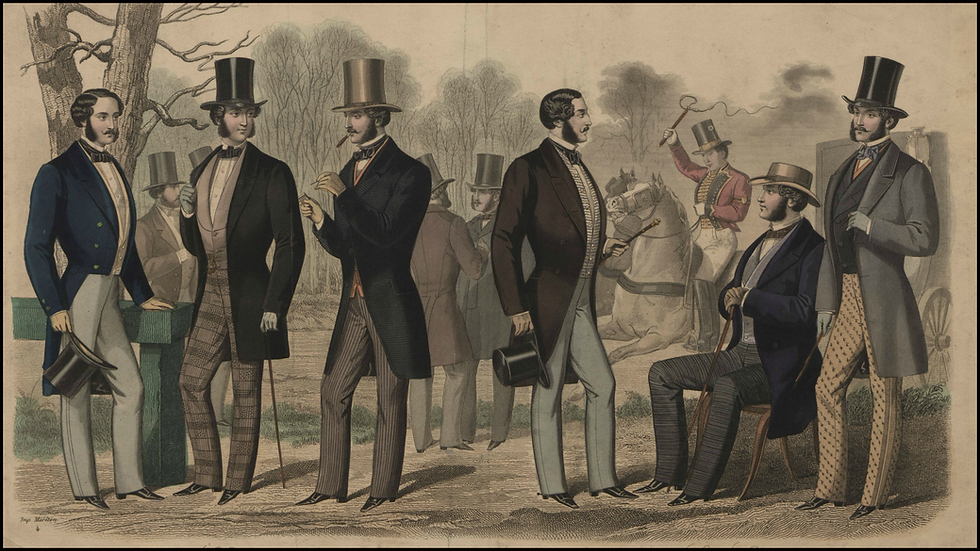

The Slow Death of Decorative Masculinity

As we’ve seen, there was a time - roughly from the late 17th century to the dawn of the 19th - when masculinity was measured not in beards or biceps, but in the volume of your curls, the gloss of your pomade, and the extravagance of your bows. Aristocratic men across Europe weren’t just wearing wigs; they were wearing statements - powdered perukes cascading over embroidered coats, silk stockings showing a well-turned calf, and enough scent to choke a perfumer.

This was early drag, but without the knowing wink: the height of male authority was wrapped, powdered, and tied with ribbon, the body transformed into a kind of portable theater of power.

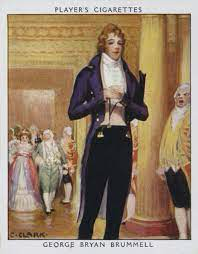

But by the early 19th century, the performance was losing its audience. The Industrial Revolution rolled in with coal dust and factory whistles, democracy began whispering about equality, and a new kind of masculinity emerged - sober, stoic, and suspicious of frippery.

The French Revolution had already lopped off both wigs and heads, and Napoleon’s soldiers had little patience for hairdos that required an army of valets. Across the Channel, Britain’s rising middle class valued restraint over ribbons, and the once-dazzling dandy became a figure to be satirized rather than emulated. Even Beau Brummell, Regency England’s last great peacock, swapped the powdered wig for immaculate natural hair and a tailored coat.

Still theatrical but stripped of the rococo excess that had once been the male birthright.

By the mid-19th century, the curls had fallen limp. Decorative masculinity - that centuries-old peacock display of wigs, lace, and scent - gave way to the sober uniform of the modern man: shorter hair, dark suit, and the emotional range of a particularly polite undertaker. The wig, once a crown of male dominance, had become a museum piece, a relic of a time when men weren’t afraid to be both powerful and fancy - often in the same breath.

Wigs for Men

History has a way of dressing us for the part we think we’re playing. Once upon a time, a man’s authority could be measured in inches - not of height, nor of any particular body part, but of hair piled like a frosted croquembouche above his brow.

A wig wasn’t just a fashion statement; it was the press release, the security clearance, the key to the executive washroom. You could be bankrupt, gout-ridden, and socially despised, but if your curls were powdered and symmetrical, you still looked like someone worth obeying.

Today we live in an age that congratulates itself on being “authentic.” The powdered curls are gone, replaced by baseball caps, techware, and sneakers that cost more than a month’s rent - performances of masculinity no less curated than the wigs of Versailles. We’ve traded the artifice of hair for the artifice of “effortlessness,” but the impulse is the same, only now the theatre is Instagram instead of the royal court. Different century, same need to curate the version of ourselves we think will sell.

And the wig? It sits in the cultural rearview mirror, part punchline, part relic, part wistful reminder that even the most absurd forms of self-presentation were once taken with deadly seriousness. In courtrooms, opera stages, drag clubs, and the occasional British parliamentary ceremony, the old tradition still breathes, powdered and perfumed, quietly refusing to be relegated to the attic. It’s a reminder that what once looked absurd was once the pinnacle of authority, and that the line between “dignified” and “ridiculous” is mostly a matter of timing.

So, here’s a tip of the hat - whether it’s to a barrister in full horsehair, a drag queen’s architectural masterpiece, or a dusty portrait of some 18th-century earl who looks like he’s hiding a small sheep under his hat.

They remind us that identity is theater, masculinity is a moving target, and dignity has always been, at least partly, a matter of good staging. The wig may have fallen out of daily use, but its ghost still hovers over every bathroom mirror, whispering: It’s not just about who you are - it’s about how you look doing it.

That sounds great

Wow, I always thought it was just an insanity that overtook Europe. Interesting how it actually had a useful purpose! To prevent bugs 🐞 !!!!! Wow unbelievable solution to a huge problem! Genius! But sadly like many things that start out as excellent solutions, turned into, well nutso theater!

Hahahaha. Thank you for the fun and for showing us another aspect of how we turn practicality into absurdity.

But I would have liked you to answer….. why did we create mayonnaise????