Speak English

- tripping8

- Aug 22, 2025

- 10 min read

A popular rallying cry of radio spin-doctors and nativist pundits alike is that in America people should just “speak English.” The phrase is usually delivered with the same smug finality as a traffic cop saying, “Move along.” But here’s the uncomfortable hitch in their perfectly starched argument: when you “speak English,” you’re actually speaking an unruly cocktail of other languages, stitched together over centuries like a thrift store quilt. You are, whether you like it or not, bilingual, trilingual, maybe even polyglot - though heaven forbid anyone in certain zip codes ever be caught admitting it.

Language, after all, is a thief. It sneaks into the night, picks the locks of other tongues, and slips away with whatever words sparkle brightest. Sometimes it comes by conquest, sometimes by trade, sometimes simply because the neighbors had a better name for “that thing with wheels.” Because that’s what languages do. They evolve, they borrow, they steal. They are living things, mongrels by design, and English is the muttiest mutt of them all. Because, as we’ll see, if purity is the goal, English failed before it ever cleared customs

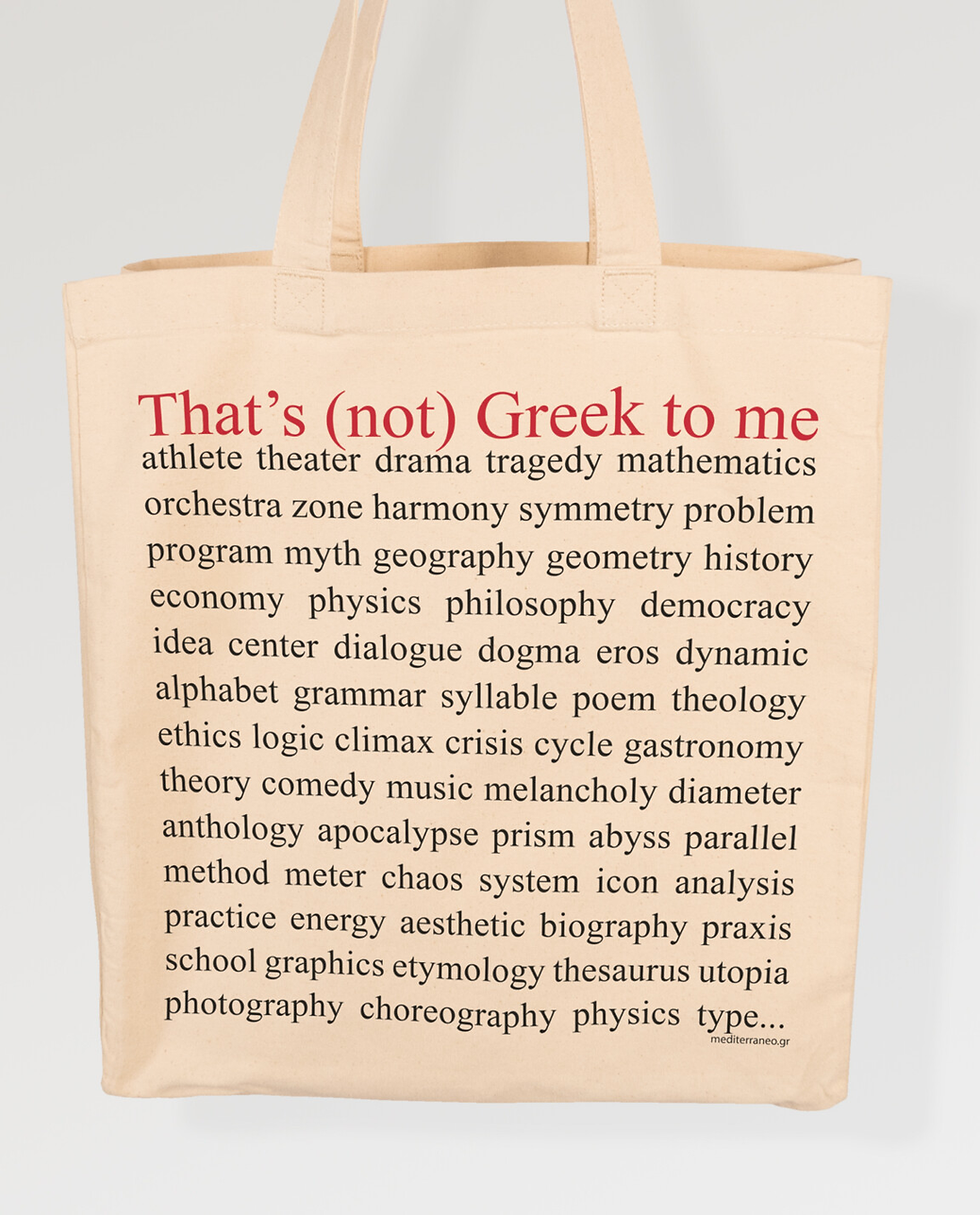

And here’s the part that might bruise a few egos: even the most ardent defenders of “pure” English - the ones who clutch their pearls at a stray Spanish word on a billboard - are unwittingly trafficking in foreign imports every time they open their mouths. That fiery “patriot” might describe their home as cozy (from Old French), enjoy their morning coffee (from Arabic via Turkish and Italian), and later binge on chocolate (from Nahuatl) without realizing they’ve just taken a linguistic world tour before lunch. The irony of it is laughable, especially since “irony” itself was also imported (Greek, via Latin and French).

Through conquest, assimilation, and, yes, immigration, English has become a restless magpie of a language - shiny bits and pieces collected over centuries from every corner of the globe. From the first Viking longship scraping onto English shores to the newest slang slipping in from social media, our vocabulary is a cultural passport stamped so many times it’s illegible. And that’s the real punchline: every time someone insists we should all be “speaking English,” they’re already doing exactly the opposite.

Pre-English Britain (Before 450 CE)

Before English ever set foot on the British Isles, the landscape was already humming with its own languages - Celtic tongues like Welsh, Cornish, Scots Gaelic, and Irish. These were the first voices of Britain, woven into daily life, poetry, and place names long before a word of English was uttered. From this era we inherit crag, bard, whisky, and even trousers - a reminder that the so-called “English wardrobe” came with Celtic stitching.

English, at this point, was still forming elsewhere, oblivious to the fact that the island it would one day claim already had a vocabulary, a culture, and a set of rhythms all its own. When the Angles and Saxons eventually arrived, they didn’t encounter linguistic emptiness waiting to be filled; they stepped into a world already richly named.

Roman Britain (43–410 CE)

When the Romans marched into Britain, they didn’t just bring soldiers; they brought a vocabulary that clung to the island as stubbornly as their stone roads. Words like wall, mile, street, and wine are all relics of empire, the linguistic equivalents of Roman ruins still scattered across the countryside. Everyday essentials - candle, cheese, chalk, tile, port - all slipped into local speech, because when a culture shows up with aqueducts and central heating, you tend to adopt their terminology.

Even after the legions withdrew, Latin refused to pack its bags. The Church carried it forward, adding words like altar, priest, school, and martyr into English vocabulary. Monks and scribes preserved the tongue long after Rome itself had crumbled, and in doing so ensured that Latin became the soundtrack of learning, religion, and official record-keeping. English, such as it was at the time, had already begun its habit of quietly pocketing anything useful.

So much of what passes for the language of authority in English is Roman in origin (justice, verdict, and legal for example) that if you stripped it away, modern courts would have little left to say.

The Viking Years (8th–11th centuries)

The Norsemen didn’t just raid monasteries and coastal villages; they also left behind a hefty cargo of vocabulary. From sky and egg to husband, knife, and window, Old Norse gave English a set of words that feel so ordinary now, it’s easy to forget they once arrived with longships and axes.

These were not exotic imports but practical, everyday terms that settled as comfortably into English speech as the Vikings did into English soil.

The influence went deeper than a handful of nouns. Old Norse reshaped grammar itself, simplifying English word endings and contributing pronouns like they, them, and their. That means entire sentences of “pure English” today were built directly on Viking scaffolding. Even the rhythm of the language shifted, adopting Norse bluntness that still makes English a sturdy, no-frills tongue compared to its continental cousins. When we speak English today, we’re merely echoing those Viking settlers who had no intention of asking permission before leaving their mark.

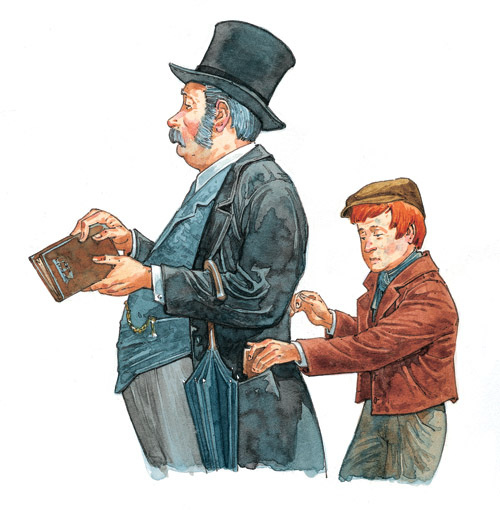

The Norman Conquest (1066 and after)

When William the Conqueror crossed the Channel, he didn’t just seize a throne - he rewired the English language.

Overnight, the vocabulary of power, law, and refinement shifted into French. The kitchen split in two: peasants raised the cow, sheep, and pig, while the nobility dined on beef, mutton, and pork. This linguistic divide was a map of class, and English has been carrying both versions of the menu ever since.

The courts and castles added their own layers. Words like court, judge, jury, royal, council, and government poured into English, giving the language its official, dignified gloss. To speak French was to speak authority, and for two centuries English survived mostly as the tongue of commoners, patched and stitched with borrowed finery from above. The so-called mother tongue was, for a long stretch, the stepchild at its own table - half peasant, half aristocrat, equal parts plow and palace.

Medieval Trade & Arabic Influence (12th–15th centuries)

As Europe reached outward through trade, conquest, and scholarship, English quietly padded its vocabulary with Arabic. From the markets came sugar, cotton, saffron, and coffee; from the scholars, algebra, zero, cipher, and alchemy. These weren’t ornamental words but necessities, absorbed as quickly as the goods themselves. The caravans may have been distant, but their cargo spilled directly into English speech.

The influence arrived indirectly, often filtered through French or Spanish, but the origin was unmistakable. Words like admiral, magazine, and tariff reveal how closely language followed commerce and exploration. Even the sciences carried the imprint, with Arabic texts serving as conduits for Greek knowledge that Europe had largely forgotten until it was handed back, annotated and improved upon. English, ever opportunistic, pocketed both the discoveries and the terms.

What emerges from this period is a language that could not pretend to stand apart from the world around it. Every exchange, whether of goods or ideas, left a trace in its vocabulary. By the late Middle Ages, English wasn’t so much an island language as an international smorgasbord.

And that was before anyone had invented the word smorgasbord (Swedish, in case you were wondering).

The Renaissance (15th–17th centuries)

With the revival of classical learning, English turned eagerly back to Greek and Latin, mining them for words that made the language feel more refined, more intellectual, more worldly. The printing press and the growth of scholarship created a hunger for vocabulary, and classical tongues obliged. From Latin came annual, manual, illustrate, index, exotic; from Greek, words like democracy, theatre, chaos, physics, and philosophy entered the fold.

This was also the age of Shakespeare and his contemporaries, writers who mixed the loftiness of classical imports with the rough-hewn sturdiness of older English. They coined freely, bent words to their will, and in the process expanded the expressive capacity of the language to levels it had never reached before. To read the plays today is to see English mid-transformation, trying on new clothes at a dizzying pace.

The Renaissance left English with a double nature: practical and plainspoken on one hand, ornate and polysyllabic on the other. In its eagerness to absorb, it became a language capable of speaking both to the marketplace and the academy, sometimes within the same sentence. What passed as sophistication was, in truth, just another layer of borrowed speech.

The Colonial Grab Bag (16th–19th centuries)

As English ships fanned out across the globe, the language followed, collecting vocabulary as diligently as it collected territories. From Spanish came patio, mosquito, canyon, and tobacco. Italian contributed opera, piano, and balcony, while Dutch offered yacht, cookie, and skipper. Even the more remote encounters left traces: coyote, avocado, and chocolate arrived via Nahuatl; shampoo, bungalow, and pajamas came from Hindi and Sanskrit.

These weren’t just curiosities tucked away in dictionaries - they became the words of everyday life. A cup of tea from China, a bungalow in India, a mosquito in the Caribbean, a piano from Italy: the vocabulary of empire was also the vocabulary of the home.

English became a ledger of colonial encounters, each word carrying the faint outline of a journey from elsewhere.

By the time English had made its colonial rounds, an afternoon snack could easily involve tea (Chinese), chocolate (Nahuatl), and a cookie (Dutch). The words that felt most natural on English lips were often those gathered furthest from its shores, - proof, we guess, that imperialism at least made teatime interesting

Immigration & Pop Culture (19th–20th centuries)

When the British Empire scattered English across the globe, they thought they were seeding loyalty to crown and country. What they actually did was set the stage for English to be hijacked, refashioned, and - eventually - Americanized. Because once the language washed up on U.S. shores, it shed its powdered wig and started reinventing itself.

From that point on, English was no longer just England’s export - it was America’s playground. And Americans remixed the language until even the British needed subtitles.

But that remix would have never happened without the immigrants who poured fuel on that reinvention and helped to create “American English”. Every wave of arrivals - Irish, Italian, Yiddish-speaking Eastern Europeans, Chinese, Mexican - brought their own lexicons, which slipped easily into American speech. Banjo (West African), mosquito (Spanish), schmooze (Yiddish), boondocks (Tagalog), pizza (Italian), kindergarten (German), rodeo (Mexican Spanish) - each is a linguistic souvenir from somebody else’s homeland. The U.S. never bothered to curate these imports; it just tossed them in the pot and called it dinner.

Then came pop culture, which did for English what Hollywood did for suburbia: standardized it while pretending it was spontaneous. Jazz, baseball, Broadway, Hollywood, advertising - all churning out slang, catchphrases, and ready-made idioms. Television was especially potent. Sitcoms like Seinfeld didn’t just entertain; they furnished English with whole new categories of speech: yada yada, close talker, double-dip, shrinkage. These so-called “Seinfeld-isms” proved that a group of neurotic New Yorkers could alter the language of a nation.

The irony, of course, is that modern American English - the very thing people think they’re protecting when they bark about “speaking English” – has actually been stitched together from immigration, pop culture, and global borrowings. Proof that American English thrived not by purity, but by porousness.

The Present Day (21st century & the Internet)

By the time the 21st century rolled in, American English was less a language and more a mish mash of cultural borrowings. Hip-hop mainstreamed African American Vernacular English into global slang - bling, dope, woke. Technology added another layer, tossing in acronyms (LOL, BRB), Silicon Valley jargon (hashtag, unfriend), and gamer slang (cosplay, respawn). The internet didn’t just accelerate language change; it put the whole thing on steroids, making yesterday’s meme today’s dictionary entry.

Globalization kept the conveyor belt running. Sushi, karaoke, feng shui, yoga, café au lait, tapas, déjà vu, emoji, avatar, meme - these weren’t niche imports but everyday menu items in the American lexicon. English has never been shy about stealing words and passing them off as native-born. Now, with TikTok trends (rizz) and K-pop fandoms (stan) feeding the language as fast as Wall Street can trademark a buzzword, the pace is relentless.

And yet, for all its unruly growth, American English still manages to masquerade as a fixed thing, a cultural anchor that some people claim must be preserved against contamination.

But this “contamination” is the very process that has always kept English alive. Without it, English wouldn’t be English at all - it would be a museum piece, embalmed in glass, admired but never spoken.

Speaking English

The irony, of course, is that the people shouting loudest about “speaking English” are usually the ones least acquainted with the thing they’re defending. English has never been a fortress - it’s a sponge. A thief. A constant improvisation by anyone who happened to pass through. Every time you say street or mile, you’re speaking Latin. Every time you raise a glass of whisky, you’re speaking Gaelic. And when you put on trousers in the morning, you’re dressing in Celtic. Every word you speak is a ghost of someone else’s history, a reminder that language, like culture, is never truly owned. It’s borrowed, reshaped, and passed along.

But try telling that to the self-appointed gatekeepers of “pure” English, the ones who mistake their high school grammar books for holy scripture. They don’t want history; they want a weapon. But their weapon of choice is hollow. When they complain about “foreign influence,” they’re doing it in a tongue shaped by Vikings, Romans, Normans, Spaniards, and anyone else who ever bothered to land a boat.

Meanwhile, the rest of the world just keeps talking. New slang, new phrases, new words - they bubble up from immigrant kitchens, internet forums, TV sitcoms, and hip hop tracks. Yesterday it was bungalow and pajamas from India; today it’s bling from rap and yada yada from Seinfeld. Tomorrow, who knows? English isn’t an oak tree rooted in one soil - it’s driftwood, carried by the currents, gathering carvings from every shoreline it washes against.

And maybe that’s the real discomfort. English is a ledger of debts America can never repay, a reminder of how porous the borders really are. You can build walls, you can pass laws, but you can’t police a language that survives by trespass. The words will keep coming, and English will keep swallowing them whole. That isn’t contamination. It’s the only reason the language is still alive. And the ones demanding purity? They’ll still be shouting into the wind - in a language stitched together from a thousand borrowed tongues. Always was. Always will be.

Wow, I have never gave it much thought, but thanks for the “obvious” explanation! It’s so funny but how many times have you looked up a word and in the definition, it’s states, comes from the Latin word for … like Polyglot …. Origin from Medieval Latin …..

While this post is brilliant in its simplicity, I doubt it will change their pea brain bias! But will give it a try!

Thank you so much for reminding me (my English teacher, Mrs Beatriz, in elementary school covered this topic) that “speaking English” is like our country: a hodgepodge of immigrants (minus of course the indigenous people of North America) and we should celebrate our differences instead of judging them.

I…