Monuments to Ourselves

- tripping8

- Oct 31, 2025

- 13 min read

There’s something almost touching about humanity’s obsession with permanence. We stack stones, pour concrete, and weld steel as if the sheer weight of our buildings might keep time itself from slipping away. Each civilization, in its turn, has left its calling card - a pyramid, a wall, a canal - saying, we were here, in case the future should forget. Of course, the future always does.

Yet we keep at it. We drag rivers from their beds, slice mountains in half, and pave deserts into submission. We call it progress, though much of it looks suspiciously like a midlife crisis with a global budget. The pharaohs had slaves; we have committees. The difference is largely semantic. Somewhere along the way, construction became our species’ collective therapy - loud, dusty, and inevitably over budget.

And what monuments they are. Entire cities have been designed to impress gods that no one worships anymore. Highways stretch like veins across continents, carrying truckloads of purpose and a lingering scent of regret. Skyscrapers pierce the clouds to remind everyone who’s in charge, though they tend to wobble at the first sign of an economic downturn. We measure our worth in meters and tons, in how deeply we can carve our initials into the face of the earth.

But impact, as it turns out, is a trickier word. Sometimes it’s measured in how a single project reshaped the world; other times, in how it merely reshaped our illusions about ourselves. And sometimes it’s not the building that leaves the impression, but the hole left behind.

A hole that no amount of drywall or gold leaf could cover up.

The Great Pyramid of Giza - A Monument to Eternity

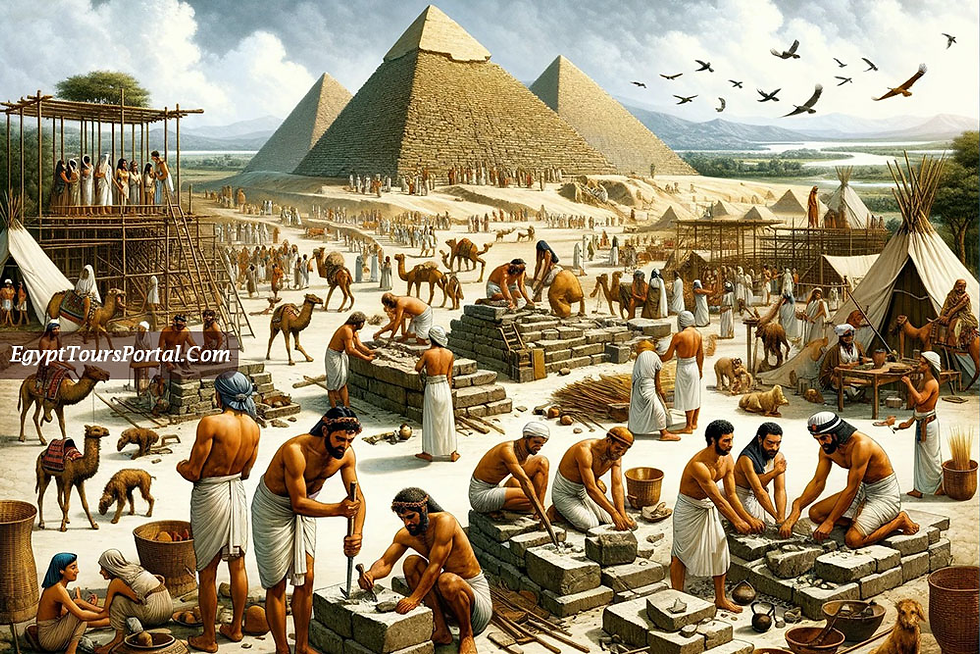

It began with a fear of being forgotten. The Great Pyramid of Giza was not built to house a body so much as it was an empire’s way of saying, we will not go quietly. Humanity’s first major attempt to outstare death - and, in some ways, it worked.

For nearly 4,000 years it stood unchallenged as the tallest structure on Earth, a record no one thought to challenge until someone invented steel and the concept of paid overtime.

Roughly 2.3 million limestone blocks were dragged, hoisted, and wedged into place, each weighing as much as a moderately sized elephant. No one knows exactly how it was done, though every theory involves a staggering amount of human exhaustion. The slaves-versus-skilled-labor debate misses the point entirely; whether by whip or by wage, the real miracle is that so many people agreed to spend decades helping someone else live forever.

Even now, the Great Pyramid endures not just as an architectural feat but as a psychological one - the first great monument to our refusal to accept impermanence. The earliest expression of that distinctly human impulse to leave behind something massive, immovable, and ostentatious enough to prove we mattered. It’s less a tomb than a declaration, a stone footnote to the modern ego: oversized, overconfident, and desperately hoping for immortality.

The Roman Roads - Immortality thru Infrastructure

If the Egyptians built to defy time, the Romans built to manage it. Their roads - over 250,000 miles of them, straight and durable - stitched together a continent so efficiently that pieces of it are still in use today, long after the empire itself collapsed under the weight of its own self-confidence.

It’s an irony the Romans might have appreciated: their engineers achieved what their emperors could not - longevity.

These roads were not romantic. They were instruments of control, laid down to carry armies, taxes, and the illusion of order. Rome paved Europe the way a bureaucrat fills out a form: relentlessly, with quiet conviction, and without ever considering who might have to live with the result. Each stone was a signature of empire, each milestone a quiet assertion that civilization was not a place but a direction - toward Rome, inevitably, inexorably. The phrase all roads lead to Rome wasn’t civic pride; it was policy.

Centuries later, traces of those roads still run through pastures, suburbs, and motorways - a skeletal map of ambition that refuses to fade. They endure as proof that power isn’t just about armies and emperors; it’s about access. Modern empires build data cables and shipping routes, but the principle remains the same: control the access, and you control the story. The Roman Empire is gone, but the infrastructure remains - silent, straight, and utterly certain it was right.

The Great Wall of China - A Monument to Paranoia

The Great Wall of China was never meant to keep people out so much as to convince those inside that they were safe. The theory was simple: fear, if properly organized, could be used to control. Over centuries it grew from scattered fortifications into a single, improbable idea carved across the land - 13,000 miles of stone, tamped earth, and anxiety.

Empires rise on confidence and aspiration, but they build walls out of fear and doubt.

It’s often called the only manmade structure visible from space, though that’s mostly untrue. What is visible - from orbit or otherwise - is the idea behind it: that security can be engineered. Millions of laborers, soldiers, and convicts spent centuries hauling earth and granite up impossible slopes to defend a border that kept shifting anyway. The Wall succeeded, just not at what it was meant to do. It didn’t stop invasions, but it did create the most enduring metaphor for human insecurity in history.

To walk along it today is to feel something between awe and futility.

It stretches across deserts and mountains, silent and eroded, less a defense than a confession. The Wall endures not so much as a triumph of architecture but as proof of an ancient and ongoing delusion: that control, no matter how well-built, can ever outlast fear.

The Transcontinental Railroad - A Monument to Motion

If the Great Wall was built to keep the world out, the Transcontinental Railroad was built to stitch it together - though mostly for the benefit of those holding the needle. In the mid-19th century, the United States still raw and half-imagined, decided that the best way to conquer its vast interior was to run a straight line through it. The idea was simple enough: connect the Atlantic to the Pacific by rail – cutting through wilderness, bisecting plains, and ignoring treaties - and you could turn half a continent into a single, manageable thought. It wasn’t so much an act of connection as an assertion: that geography was just another obstacle waiting for a timetable.

The dream was dressed up as destiny, but it was really logistics. It was also a kind of violence - clean, efficient, and heavily subsidized. Thousands of immigrant laborers - mostly Chinese in the West, Irish in the East - worked through snowstorms, dynamite, and dehydration to meet in the middle, while financiers took credit and profits in equal measure. Entire landscapes were reordered so trains could run on schedule. The buffalo disappeared, the land was parceled, and the continent itself seemed to exhale under the weight of new ambition.

At the golden spike ceremony in May of 1869, they said two oceans had finally been joined.

A journey that once took over a month by covered wagon could now be done in just four days. What they didn’t mention was how many worlds had been severed in the process. The railroad was less about joining than about owning. It turned distance into property, time into money, and the open frontier into a ledger line. And though the trains no longer thunder through the plains as they once did, their echo lingers - a rhythmic reminder that in America, at least, connection has always been less about bringing people together and more about making sure everything, eventually, gets delivered.

The Panama Canal - A Monument to Rearrangement

By the early 20th century, the world had grown impatient with its own design. South America was in the way, time was money, and someone decided the planet could use a little editing. Thus came the Panama Canal - a 50-mile incision across the spine of a continent, carved not out of necessity but out of annoyance.

It was humanity’s declaration that geography, like everything else, could be improved with enough money, machinery, and misplaced confidence. The moment we stopped building on the planet and started building against it.

The French tried first and failed spectacularly, losing fortunes, equipment, and roughly twenty thousand lives to mud, malaria, and hubris. The Americans, with characteristic optimism and access to dynamite, took over in 1904 and finished what nature had the good sense to leave intact. Entire mountains were vaporized, rivers rerouted, and a workforce imported from across the Caribbean to sweat and die in a land most of them would never see again. It wasn’t construction so much as surgery performed by committee - the world’s first continental lobotomy.

When it opened in 1914, the Canal shortened global trade routes, redrew maps, and proved that ambition could, literally, move mountains.

Trade flowed, empires swelled, and humanity congratulated itself on outsmarting geography. But beneath the triumph was something darker - the quiet certainty that the planet could be managed like an asset, improved upon like a quarterly report. Even now, ships slip through that narrow scar between oceans, carrying the same illusion that built it: that control, once achieved, can be made permanent.

The Interstate Highway System - A Monument to Convenience

By the mid-20th century, America had grown tired of distances that still felt like distances. The world had been conquered, rearranged, and subdivided - now it just needed to be made drivable. The Interstate Highway System was billed as progress: 48,000 miles of smooth asphalt, linking coast to coast in the name of freedom and fuel efficiency. In truth, it was less a transportation project than an infrastructure-sized expression of national impatience.

President Eisenhower sold it as defense - a network designed to move troops and evacuate cities in case of Soviet attack. What it really moved was everything else: families, freight, ambition, and suburban sprawl. Towns were split, neighborhoods erased, and downtowns gutted in the name of speed. The new America wasn’t meant to be lived in so much as driven through. Gas stations replaced gathering places; exits replaced destinations. It was progress by demolition - convenient, anonymous, and endlessly self-replicating.

The Romans paved to rule, the Americans paved to escape. Yet the result was much the same: control disguised as connection. Even now, the interstates hum beneath the weight of their own design - a vast circulatory system that keeps the country alive mostly by keeping it moving. It’s hard to say whether the highways united America or merely stretched it thin. Either way, the destination was always the same: somewhere else.

The Three Gorges Dam - A Monument to Scale

By the time the Three Gorges Dam was completed in 2012, China had long since mastered the art of turning necessity into spectacle. Officially, it was built to control flooding, generate power, and modernize the heart of the Yangtze River.

Unofficially, it was built because it could be. Stretching more than 1.4 miles across and standing 594 feet tall (181 meters), it’s the largest power station on Earth - an engineering project so colossal it rearranged the planet’s rotation by a fraction of a second. Humanity, it seemed, had finally managed to leave a dent big enough to show up in physics.

The numbers are staggering: 32 generators, 39 trillion gallons of water displaced, over a million people relocated. Entire towns vanished beneath the reservoir, their histories drowned in the name of national progress. Environmentalists called it catastrophic; officials called it “necessary.” And perhaps they were both right. The Dam did what dams do best - it held back chaos, but only by creating a new kind. The Yangtze still floods, just differently now, on a schedule.

One can’t help but admire the scale, even as it feels vaguely obscene - the audacity of humans who saw a 3,900-mile river and thought, “We can fix that.”

The Great Wall was built to keep the world out; the Three Gorges Dam was built to hold it still. Both succeeded, in their way, at turning anxiety into architecture. Time, of course, wasn’t impressed by one, and - eventually - won’t be by the other.

The International Space Station - A Monument to Orbit

If the Panama Canal was a cut through the Earth, the International Space Station was our first real attempt to cut loose from it. By the late 20th century, humanity had already carved the planet to its liking - dammed its rivers, paved its wilderness, rearranged its continents for convenience. The next logical step was to leave. The International Space Station was built as proof that we could outgrow gravity, or at least rent some space above it. A joint project between rivals, it was part laboratory, part diplomatic stunt - a fragile outpost of civility, circling a world that still hadn’t managed much of it.

Up there, 250 miles above the noise, everything became precious: air, water, conversation - everything had to be recycled, rationed, and justified - even breath. Humanity finally learned that conservation could actually keep us alive. Nations that could barely agree on lunch down below managed to share oxygen, wiring, and the occasional freeze-dried meal. It was a triumph of cooperation mostly because there was nowhere else to go. Suspended between sunrise and sunset sixteen times a day, the Station became the world’s most expensive waiting room - proof that even in orbit, bureaucracy finds a way.

For more than two decades, it’s drifted above us, a $150 billion reminder that escape doesn’t guarantee progress. From the ground, it glides overhead like a slow confession, circling a planet still divided by the same borders its builders once tried to escape; its quiet orbit a reminder that leaving Earth isn’t the same as outgrowing it. When it finally falls, as all monuments do, it won’t mark the end of exploration so much as another orbit completed. Maybe then we’ll call it what it always was - a monument not to space, but to the stubborn gravity of human hope.

The Internet - A Monument to Connection

When humanity finally grew tired of building outward, it turned inward - into the quiet circuitry of its own collective mind. After centuries of pyramids, canals, and steel, we began constructing something less tangible but infinitely larger: a world made of words, images, and impulse. The Internet wasn’t designed like a monument; it became one, sprawling invisibly across oceans and time zones, a single nervous system pulsing beneath our feet.

If the Transcontinental Railroad turned distance into property, the Internet turned information into currency - and confusion into its natural byproduct.

Born from military caution and academic optimism, it promised to unite what walls and empires had divided. And in a way, it did - a trillion digital threads binding us into one anxious organism. But connection, it turns out, isn’t the same as coherence. For every bridge it built, it quietly dug a moat: between truth and noise, knowledge and certainty, us and ourselves. The dream of a global village became a crowded plaza of mirrors.

A place where everyone talks and no one listens, where facts are negotiable and loneliness travels at the speed of light.

If the International Space Station was our attempt to rise above ourselves, the Internet is our attempt to replace ourselves entirely - to trade memory for metadata, presence for performance. It’s the latest and most pervasive monument to human longing: the need to be seen, known, and endlessly refreshed. Someday it too will fade, or fracture, or be replaced by something faster. But until then, it hums ceaselessly, our most faithful reflection - a shimmering, global reminder that we’ve never been closer together nor felt more efficiently apart.

The Ballroom - A Monument to Self-Importance

They’ve torn down the East Wing of the White House.

In its place, a ballroom - vast, gold-leafed, and unapologetically Versailles-like. A hall not for governance, but for grandeur. The rendering is large, the rhetoric larger, and the demolition was carried out with the same certainty - and the same absence of empathy - with which executives order a boardroom refit. Where once First Ladies worked on humanitarian projects and staffers scurried unseen, there will now be chandeliers heavy enough to bend light, a ceiling painted to flatter the gaze from below, and enough marble and gold-leaf to remind the guests that modesty, like truth, is no longer in fashion.

The official story is modernization. Functionality. Expansion. Of course, every empire rehearses the same script before the curtain falls. But the truth is simpler: power grows restless when it runs out of enemies, so it begins renovating itself. The East Wing’s demolition wasn’t an act of improvement - it was an exorcism of humility. To build a ballroom where a workplace “for the people” once stood is to declare that the spectacle now matters more than state. What’s been sacrificed was the sense that the White House is a shared civic space rather than a branded estate.

It’s not the first time a ruler has mistaken reflection for legacy. Pharaohs lined their tombs with gold for the same reason - to prove, at least to themselves, that grandeur might outlast mortality. Spoiler alert - it doesn’t. The stones erode, the names fade, and sooner or later the wind whistles through the cracks. This new ballroom will gleam for a while, its mirrors burnished by flashbulbs and applause. But the light will dim, as it always does, and what remains won’t be the glittering promise of importance - only the echo of a man who mistook spectacle for salvation.

Monuments to Ourselves

We’ve been stacking stones and pouring concrete for five thousand years, trying to make permanence out of the temporary. From the pyramids to the cloud, every generation lays down its own proof of existence - a kind of architectural resume for the gods. We tell ourselves these things matter: the walls, the rails, the wires. But give them time and they all start to look the same - ruins with better PR.

Maybe that’s the point. The monuments aren’t about what they celebrate but what they confess. Every wall is a mirror; every bridge, a wish. We build because we’re terrified of being forgotten, and the higher we pile our ambitions, the louder that fear hums beneath the surface. The Great Wall, the Canal, the Internet - all just different verses of the same hymn to human insecurity.

And now, the ballroom.

Another man trying to buy his way into history with chandeliers and too much gold trim. The tools change, the instinct doesn’t. The powerful have always tried to outbuild their own mortality; they just change the style every few centuries. Pharaohs had pyramids. Dictators have statues. Now, chandeliers the size of the ache we’re trying to fill. We don’t really build monuments to greatness - we build them to hide the cracks. To convince ourselves that we were right, that the story ends with us, that this time the marble won’t crumble, and the name won’t fade.

But it will. They always do. Time doesn’t care who’s in the photo op. The pyramids shed their casing stones, the railroads rust, the servers fry, and someday that ballroom will gather dust, its mirrors dull and lifeless. Maybe someone will walk through the ruins and wonder what kind of people we were: so desperate to be remembered that we forgot to be worth remembering. Because no matter how many walls we build, the horizon will always belong to someone else.

Wow some for progress, some for protection, some for beauty, some, because we can, some because we ask “can we?” and some for gigantic ego…. Embarrasingly gigantic orange egos.

Love this, "We call it progress, though much of it looks suspiciously like a midlife crisis with a global budget."