Animals on Trial

- tripping8

- Aug 8, 2025

- 13 min read

There’s something almost touching about the human obsession with order. We alphabetize spices we haven’t used in years, color-code sock drawers, and insist on queueing even in the absence of anything worth queuing for. We draw invisible lines through oceans and deserts, declare them borders, and then kill one another for crossing them. We construct entire systems - legal, moral, theological - on the assumption that the universe, too, must be cataloged, labeled, and held accountable. It’s our little fantasy of fairness. Of course, fairness is rarely what we’re actually after. What we really want is someone to blame.

And so, we blame. We blame the weather for our moods, the stars for our decisions, and the Wi-Fi for our lack of charm. We blame politicians, naturally, but also baristas, parking meters, and the concept of Mondays. When things go wrong - and they always do - we reach for a scapegoat with the panicked grace of a dinner host trying to extinguish a grease fire with a bottle of cologne. And if no scapegoat is readily available, we’ll simply invent one. Preferably one that can’t defend itself.

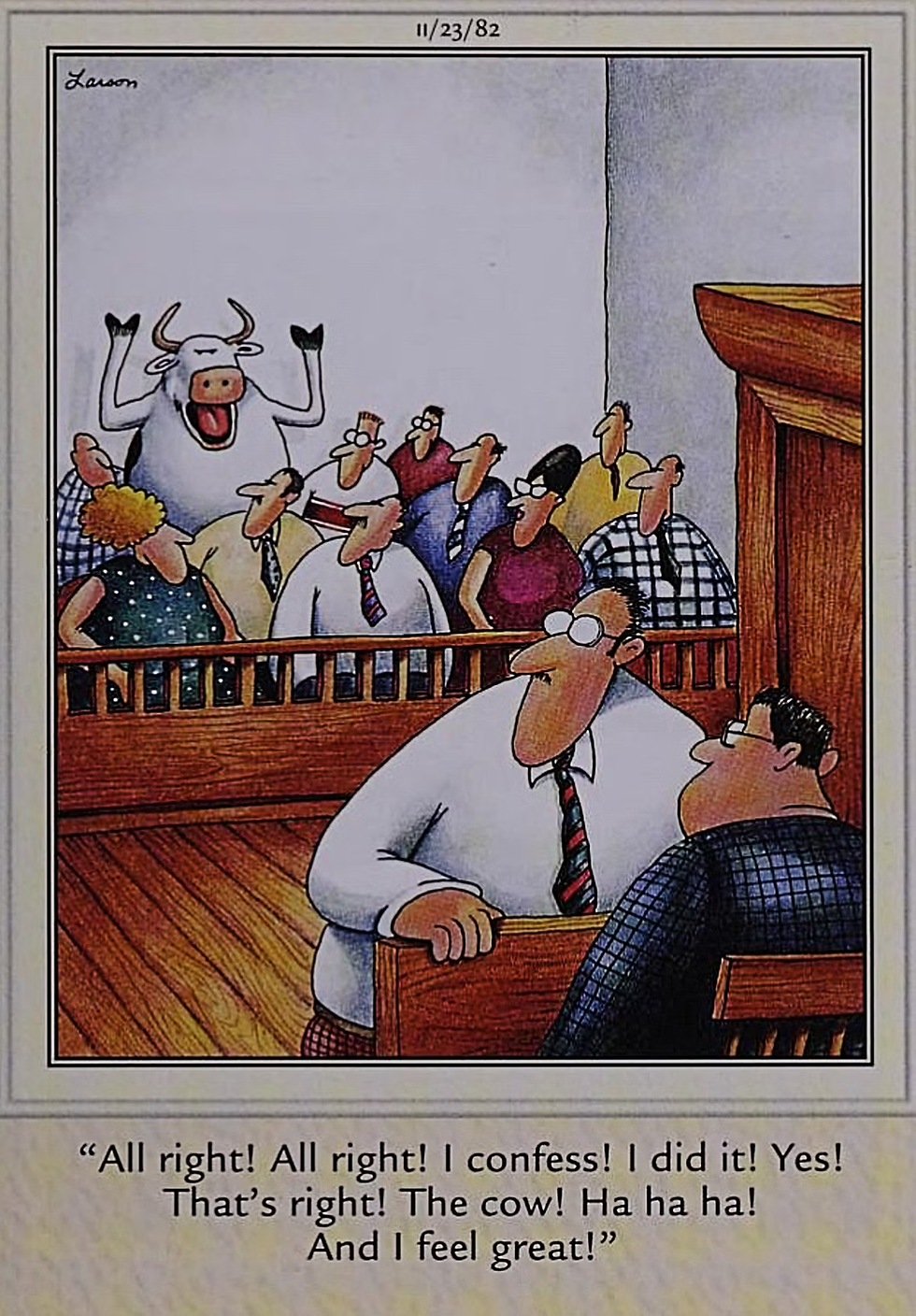

Which brings us, as most things inevitably do, to the courtroom. That sacred, wood-paneled stage upon which justice is meant to pirouette in blindfold and ballet slippers, but more often appears drunk, under-rehearsed, and more than a little bit vengeful. The court is where we summon the accused, list their sins, and thump gavels in the name of truth. It is also, on occasion, where we have prosecuted grasshoppers for eating too much barley, pigs for murder, and roosters for laying suspiciously unholy eggs.

Yes, it seems that history is dotted with curious little episodes in which animals - and sometimes insects - were dragged before the bar of justice, accused of crimes ranging from the agricultural to the metaphysical. Some were tried with all the solemnity afforded to a bishop or a thief; others were merely humiliated before execution. This, then, is a small, and perhaps unnecessary, compendium of a few of the moments when humanity looked into the blank, indifferent eyes of nature - and decided to sue.

The Pig of Falaise

In 1386 in the French town of Falaise, a sow was put on trial for what the records solemnly refer to as the “willful murder and partial consumption” of a human infant. The details are as unpleasant as they are oddly bureaucratic: the child had been left alone, the sow and her six piglets had wandered in, and what followed was judged not as an accident or unfortunate lapse in animal husbandry, but as a criminal act. Not content with mere slaughter, the authorities brought the sow before a secular court, where she stood trial much like any other accused murderer complete with legal counsel.

She was found guilty and sentenced to death by hanging. But this was not to be a quiet execution. In an effort to uphold dignity - whose, it’s unclear - the sow was dressed in a crisp white blouse, the same kind worn by condemned humans, and paraded through the town square. The people of Falaise gathered in full force and farmers from the surrounding countryside arrived with their own pigs in tow, apparently under the impression that witnessing the spectacle might instill a moral lesson. Whether any of the pigs later adjusted their behavior is not on record.

As for the sow’s six piglets, they too were arrested and briefly held as accessories to the crime. The court, however, after some deliberation, chose to acquit them on account of their youth and the corrupting influence of their mother. It was determined that they had merely followed her bad example, and since they were quite young, possibly unaware that the snack in question was, legally speaking, a person. They were spared the noose - a gesture of clemency that, in its own strange way, suggests medieval justice had a soft spot for youth, if not for species.

Barley Eating Rats

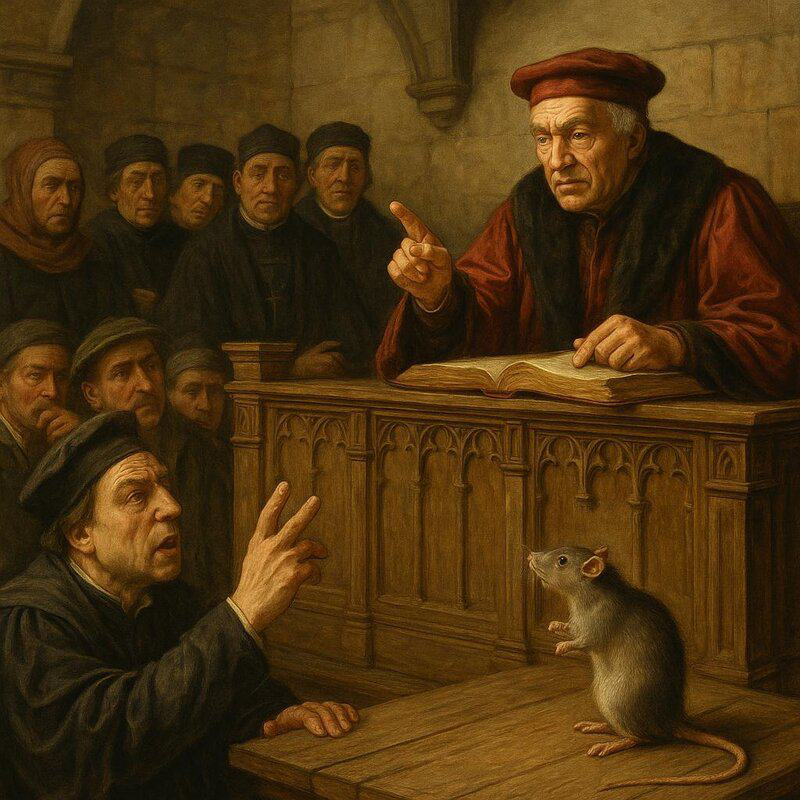

In the year 1508, the barley fields of Autun, France, fell victim to a criminal element of the wiliest variety: rats. The local clergy, deeply inconvenienced and apparently with very little else on the docket, issued a formal summons to the rodents, accusing them of wanton destruction of crops and a general disregard for ecclesiastical property. Should the rats be found guilty - and this was a very real possibility - they faced excommunication.

Not from polite society, mind you, but from the Episcopalian Church itself, which raises the question of whether the rats had ever officially joined.

Enter Barthélemy de Chasseneuz, a young and exceptionally well-prepared lawyer appointed to represent the accused. He took to the role with the kind of unshakable earnestness that suggests either great principle or great boredom. When the rats failed to appear in court (as might be expected), the judge proposed to try them in absentia. De Chasseneuz objected. His clients, he argued, had the right to appear and defend themselves. He requested that a summons be sent to each defendant. The court agreed and summonses were then dutifully posted in all neighboring towns, low to the ground, so that the intended recipients could see them.

Yet still the rats did not come. De Chasseneuz, undeterred, informed the court that his clients were willing, but afraid. The roads, he explained, were teeming with cats and dogs, many of whom had made their personal feelings toward rodents violently clear.

Unless the court could guarantee their safety en route to trial, the rats would remain in hiding. When the judge’s order to confine all local pets still failed to inspire compliance the proceedings quietly fell apart. The rats were neither convicted nor excommunicated. As for de Chasseneuz, he went on to become one of the most respected jurists in France.

Termites in Brazil

In 1713, in the Brazilian town of São João de Ipojuca, a colony of termites found themselves entangled in what must be the strangest land dispute in ecclesiastical history. The insects, in their blind and irreligious way, had taken to gnawing through the sacred wood of a local monastery - altars, beams, vestments chairs - apparently without the slightest regard for the sanctity of the materials or the sentiments of the clergy. The monks, finding their pious furnishings reduced to dust, did what any reasonable institution would do in such a situation: they filed a formal complaint and brought the termites to trial in church court.

The case was handled by ecclesiastical authorities, who approached it with the solemnity of a heresy tribunal.

The termites were accused of desecrating holy property, which, in a spiritual sense, constituted not just vandalism, but an affront to God. They were summoned to appear - though no one expected them to arrive in full procession - and when (predictably) they did not, a cleric was appointed to represent their interests. Insects, after all, were believed to be part of God’s creation and therefore subject to both His mercy and His law. The defense argued that the termites were merely acting on instinct, without malice or moral agency.

The court, in a rare burst of diplomatic creativity, chose not to excommunicate or exterminate the offenders, but to negotiate. A compromise was proposed: the termites would be granted an alternative parcel of land outside the monastery walls, free of sacred furnishings and presumably rich in delicious cellulose. The hope was that, relocated and appeased, they would cease their incursions. The agreement was read aloud in Latin and declared binding. Whether the termites honored it remains uncertain, though no further charges appear in the record.

The Rooster of Basel

In 1474, the city of Basel, Switzerland found itself confronted with a grave matter of poultry and prophecy. A rooster was discovered to have laid an egg. This alone was troubling, not for reasons of biology (which, at the time, remained largely speculative), but because of a lingering medieval superstition: if such an egg were incubated by a serpent, it was believed to hatch a basilisk, a reptilian horror capable of killing with a glance and turning entire villages into uninhabitable real estate.

In short, the rooster was suspected not merely of irregular egg production, but of conspiring - however unconsciously - in a plot against humanity.

The bird was seized and brought before a secular court. No back-alley beheading or quiet disappearance here; this was a full legal proceeding, complete with public spectators and a court-appointed defender. The lawyer argued, rather sensibly, that the act of laying the egg had been involuntary and, in any case, no serpent had yet shown interest in babysitting it. The rooster, he insisted, meant no harm and likely had no idea it had done anything at all. But the court, caught somewhere between religious anxiety and theatrical obligation, was unmoved.

The verdict was swift and unmerciful. The rooster was found guilty of “unnatural behavior” and sentenced to death by fire. Its egg, deemed equally suspicious, was condemned alongside it. In a final flourish of civic symbolism, both bird and egg were burned at the stake - an execution meant less to punish than to prevent.

Centuries later, science would explain that the unfortunate animal was likely a hen with a hormonal imbalance, but in 15th-century Switzerland, the only balance that mattered was the one between fear and firewood.

The Carp of Warsaw

In 17th-century Warsaw, at a time when theology and fishmongering were only loosely distinguishable professions, a carp was arrested on suspicion of being in league with the devil. It had been pulled from the Vistula River, reportedly writhing and gasping with what some townspeople insisted were uncanny human sounds. Others claimed it had spoken - yes, spoken - uttering ominous predictions or perhaps blasphemies, depending on who was doing the retelling and how much they'd had to drink.

Such allegations, naturally, warranted immediate ecclesiastical attention. The carp was taken into custody and placed under religious interrogation. It’s unclear whether this involved holy water, intense staring, or simply shouting Psalms at the bowl, but the general consensus among the clergy was that the fish was not just of the devil, but quite possibly housing him. A full trial was convened. Witnesses were called. The fish did not testify in its own defense, which was taken, of course, as further proof of guilt.

The verdict was damning. The carp was declared a demon in disguise and sentenced to death. It was ritually executed - how exactly is lost to time, though one imagines it involved something more ceremonial than a frying pan. What matters is that order was restored, evil was vanquished, and a small but vocal segment of the Warsaw faithful could go home assured that they would not, in fact, be outwitted by freshwater seafood.

The Bees of Sueca

In the 1780s, in the sun-drenched town of Sueca, Spain, a grave case was brought before local magistrates: several villagers had been stung, unprovoked, by bees. Not just once, but repeatedly - and with what some claimed was “malicious intent.” The pain was real, the swelling dramatic, and in the absence of modern medicine or emotional resilience, something had to be done. The bees were duly summoned to court to answer for their crimes.

Now, no one expected the bees to appear in court dressed in little waistcoats, of course, but that didn’t stop the proceedings from going forward. Witnesses testified to the attacks. Some claimed they had been minding their own business; others, that they may have been throwing rocks at the hive. A lawyer was appointed to speak on behalf of the bees - though his argument largely rested on the difficulty of proving “intent” in an insect colony. The court agreed there was no way to determine which bees had delivered the offending stings. The accused were indistinguishable, uncooperative, and uniformly armed.

And so, in a ruling that would make even the most draconian legal theorist wince, the judge issued a sentence of collective punishment. The entire hive - innocent, guilty, and nectar-drunk alike - was to be destroyed. It was burned, ceremonially, in the town square, a public execution meant to restore order and deliver a stern message to other airborne malcontents. Whether the verdict had any long-term deterrent effect on bee behavior is doubtful, but for the villagers of Sueca, justice had been served.

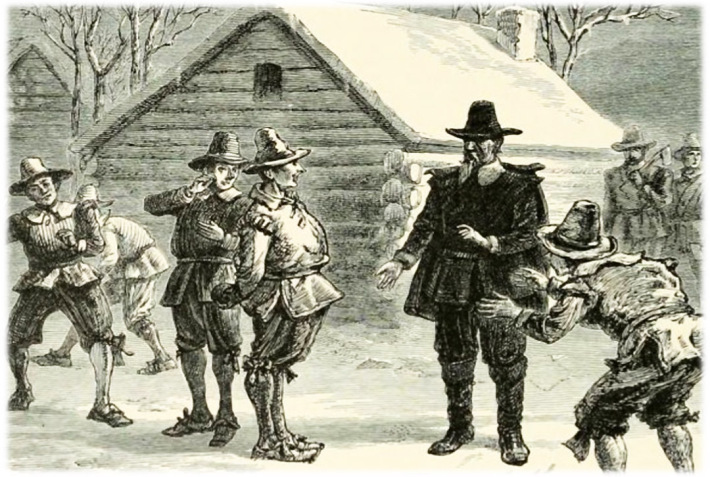

The Salem Dog Trials

The Salem Witch Trials of 1692 are best remembered for their peculiar cocktail of mass hysteria, bad theology, and unfortunate women named Goody. Less well known is that, amidst the whirlwind of spectral evidence and screaming teenagers, two dogs found themselves swept into the judicial madness. Neither was caught mid-incantation or found with tiny brooms; their crimes were far more abstract - namely, existing within barking distance of someone having a spiritual crisis.

The first dog lived in Andover, Massachusetts, and belonged to a man whose only sin appears to have been proximity. When one of the afflicted girls - those adolescent oracles of the devil’s doings - claimed the dog had bewitched her, the townspeople acted with their usual blend of decisiveness and theological confusion. The dog was shot. Upon its death, Reverend Cotton Mather reportedly announced that the animal was, in fact, innocent. This may sound merciful, until one recalls the core logic of witch-hunting at the time: if you died, you were innocent. If you lived, you were a witch. It was an imperfect system.

The second dog’s fate was no less bleak. It was said to have been tormented not by a human, but by the spirit of one - specifically, John Bradstreet, a man accused of witchcraft after being seen “riding and tormenting” the animal in spectral form.

To punish the alleged sorcerer, the villagers did what any god-fearing community would do: they killed the dog, hoping the pain would somehow travel back up the spiritual connection and harm the witch himself. Whether Bradstreet felt anything is unknown, but he left town shortly thereafter - possibly in grief, possibly in fear, or possibly because the entire town had lost its mind and was now executing household pets for metaphysical crimes.

The Trial of the Weevils

In the mid‑1500s, the vineyards of Saint‑Julien in southeastern France were ravaged by a determined swarm of weevils - tiny beetles that feasted on grapes with relentless efficiency.

The vintners, lacking insecticides but well-stocked in indignation, took the matter to the local bishop’s ecclesiastical court in April 1587. They accused the weevils of criminal trespass, theft, destruction of property, and spiritual affront to the community of winegrowers.

A formal trial ensued. The court fashionably appointed an advocate - Pierre Rembaud - to represent the insect defendants. With genuine erudition he argued that the weevils had divine precedent: that God had put the beetles on Earth and wouldn’t have created them without also providing them with proper sustenance. The prosecution responded that although the weevils may have existed before mankind, men held dominion over animals, and the creatures must not infringe upon cultivated vineyards.

After eight months of argument, evidence, and Biblical citations dressed up in law‑school flair, the court encouraged a pragmatic settlement. The townspeople offered the weevils a reserved tract of land where they might live in peace, provided they vacated the vineyards and accepted excommunication should they ever return. The weevils advocate protested: the land was sterile and wouldn’t provide enough food to sustain his clients and requested expert evaluation, delaying the process even further. In the end, the final verdict is lost - ironically eaten by insects or rats in the archives - but it seems the compromise stood, and the weevils were granted territory and tolerated, begrudgingly, in the vineyards they once terrorized.

The Honey Bear

In 2008, in the rustic outskirts of Bitola, Macedonia, a bear was taken to court for a particularly sweet-toothed crime spree. The animal - unlicensed, uninsured, and entirely indifferent to property law - had been raiding the beehives of a local farmer night after night, devouring honey with the sort of feral enthusiasm usually reserved for buffet shrimp.

The farmer, having exhausted conventional deterrents - including strobe lights and a nonstop loop of turbo-folk music, which is an assault on the senses even for humans - decided to take a more permanent measure: he sued the bear.

The case made it to court, where - due to the bear’s conspicuous absence - no defense was presented. This did not appear to trouble the judiciary. The judge ruled decisively in favor of the farmer, finding the bear guilty of repeated theft and destruction of private property. The verdict included a fine of 140,000 Macedonian denars (roughly $3,500), a sum presumably calculated by factoring in lost honey, broken hives, and the psychic toll of nightly ursine harassment.

Execution or imprisonment were not on the table, as the bear belonged to a protected species and, inconveniently, had not been apprehended. Still, a ruling is a ruling. With the convicted party both on the run and financially insolvent, the Macedonian state was left to cover the damages. Whether this set any precedent for future litigation against woodland creatures is unclear, but somewhere in the Carpathians, a bear now exists with a criminal record and a court judgment it has no plans to honor.

The Covid Curfew Cat

In the spring of 2020, when the covid curfew came to Thailand, it was applied with vigor. From 10 p.m. to 4 a.m., the streets emptied under the watchful glare of the police, who were now conscripted as both public health enforcers and reluctant nightwatchmen. Citizens caught wandering during the forbidden hours were subject to fines, jail time, or worse: public embarrassment on Facebook. It was the kind of atmosphere that made even the stray dogs lie low.

And yet, despite all this, one small, whiskered anarchist slipped through the net.

Somewhere in the hushed hours of the curfew, a small, four-legged insurgent (name withheld, possibly for legal reasons) was found prowling the streets - maskless, license-less, and fully indifferent to the emergency decree. The officers, apparently left with few options, took the kitty into custody. Paw prints were taken.

A handwritten placard was hung around its neck, announcing, “I left my home after 10 p.m. in violation of the curfew.” The cat's expression in its mugshot - somewhere between bored contempt and aristocratic disdain - was immortalized online, serving as both public warning and surreal comic relief.

It’s unclear whether any formal charges were filed, though one imagines the defendant offered little in the way of a defense. Still, in a time of airborne danger and creeping panic, it was oddly comforting to know that the law was being applied evenly - to humans, to businesses, and, when necessary, to cats.

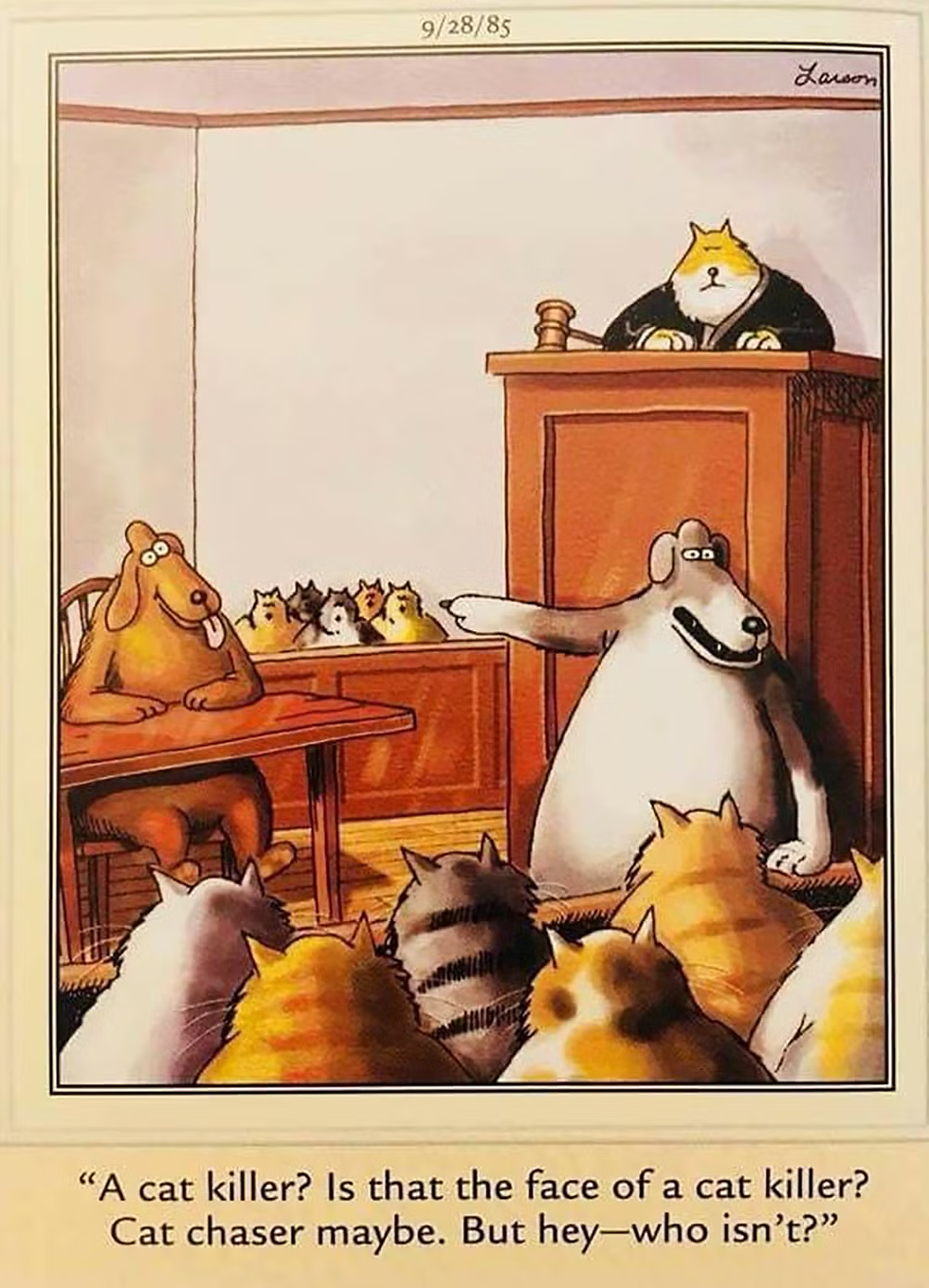

Animals on Trial

It’s tempting to laugh at these courtroom farces, and to be fair - we should. Termites receiving eviction notices. A rooster held responsible for biology. A demon carp meeting its fate at the hands of theology and a confused village council. The absurdity is the point, but the motivation behind it is as old as fear itself: when people feel powerless, they start hunting for something - anything - to blame.

You don’t haul a termite into court because you think it understands guilt. You do it because you’re desperate to make sense of a world that refuses to play fair. When crops fail, when plagues come knocking, when the boundaries between natural and unnatural blur - people look for order in the chaos. And if that means indicting a rooster for witchcraft or a cow for heresy, so be it. It’s not about justice. It’s about control. Or at least the illusion of it. These weren’t legal proceedings so much as public exorcisms - ritual theater to reassure the crowd that someone, somewhere, was still at the wheel.

Fast-forward a few centuries and the targets have changed, but the instinct hasn’t. Substitute “satanic goat” with “immigrant,” or “witch’s dog” with “algorithms,” and you’ll see echoes of these same rituals playing out in headlines and hashtags. We still crave trials, even if they play out in comment sections instead of courtrooms. We still draw up charges against things we don’t understand - or worse, against things we do, but wish we didn’t.

Maybe the lesson to be learned from all this isn’t that people once did silly things out of fear. It’s that fear hasn’t evolved much. Only the stagecraft has. So, laugh at the bee trials and the demon fish, but don’t kid yourself: we’re still lighting torches, still pointing fingers. We may not be burning beehives anymore, but every time we punish the many for the actions of a few, every time we punish the symptom instead of the disease, the spirit of those trials lives on. And if we ever do put a chatbot on the stand, I just hope someone remembers to call a cat as witness.

Chris, this is a really great piece of writing and I had no idea about this history. But oh my God unbelievable! And yes, you're right. It's humans trying to control and make meaning out of something that probably they should just take personal responsibility for. Keep up the great work. I love your blogs

To say that we, the People, are Bizarre is putting it mildly! It just goes to show…… we have to blame someone! I would hope that termites would never darken the corridors of our courthouses again, but of course, these are strange times. Maybe DJT’s hair will be sued for disturbing my peace!